Visiting the peripheral Italian city of Trieste for the first time to assess it for the Academy of Urbanism’s Great City Award, I was glad to come across travel writer Jan Morris’s final book, which she titled memorably Trieste and the meaning of nowhere. Located on a spit which juts out into the Adriatic on the north eastern coast of Italy, it is only a few miles from Slovenia, then Croatia, and the former border with Yugoslavia. It lies in the Friuli-Venezia Region, and has a current population of around 206,000. This makes it 45th in size, not much larger than in 1900 as it has been shrinking in recent years. Greater Trieste has a population of 260,000, and the city has been expanding into the hills above it known as the Karst, which can be hard to reach when the winds blow.

Trieste, rather like Liverpool, is a relic of a lost Empire. On a beautiful bay edged in by the steep limestone plateau, Trieste owes its existence as a great European city to the Austro Hungarian empire, and particularly Empress Marie Theresa. She turned the relics of a small Roman city into their imperial port, with large classical buildings and a formal grid of streets. The city attracted a cosmopolitan population, including writers like James Joyce, who enjoyed its liberal atmosphere, bars and cafes. The port was then as important as Hamburg, a major connection between Europe and Asia, and was once known for the smell of roasting coffee at Illy’s plant. It was essentially a commercial town. Karl Marx commented that it had the advantage, like the USA, of ‘not having any past’.

However, after the end of the First World War, it was handed over to Italy, becoming part of an arc known as Mittel or Central Europe. In the Second World War it was the site of Italy’s only concentration camp, which eliminated the Jewish community, but left behind Europe’s largest synagogue.

So when the port lost trade, the banks, insurance and shipping companies contracted, and the city was left without an obvious purpose. My Rough Guide to Italy in 1999 complained: ‘A Hapsburg city ..its spirit and appearance is Central European, more like Llublijana in Slovenia than anywhere else in the region.. ‘Trieste is in a potentially idyllic setting; close up, however, the place reveals uninviting water and a generally run-down atmosphere.’ …‘ First impressions are shaped by crumbling buildings.’

Engineering a transformation

The current Rough Guide is much more positive, and there is now a choice of good hotels, such as the stylish Urban Hotel Design, where the team from the Academy of Urbanism stayed on their assessment visit. Jan Morris, returning in 2001 to a place she had known for fifty years concluded in her final book that ‘ a peculiar history and a precarious geographical situation have made Trieste as near a decent city as you can find at the start of the twenty-first century’. Trieste had benefited from the growth of international tourism, especially as visitors come from Venice through Trieste to the former Yugoslav coastal resorts. Its renaissance has also been due to ‘reinventing itself as a centre of science’. Its recent history offers lessons to other mid-sized cities faced with finding a new purpose.

The turning point may have been the election of Mayor llly two decades ago, who had run the world famous coffee business. He was succeeded as Mayor by Roberto Di Piazza, who also brought an entrepreneurial approach to city governance, and has been re-elected four times?

Like the Mayor of neighbouring Ljubljana, who he studied with as a young man, he also had run supermarkets. Hence he is expert in responding to what customers want, and the politics of making things happen. The first step was to transform the environment, by making the streets ‘clean and safe’.

The city has done well in attracting grants from the European Union, which helped in restoring the old buildings with an authentic palette of colours. The Mayor personally intervenes with owners who hold back, and helps bring the different interests together.

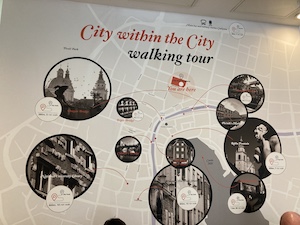

A programme of upgrading the grand squares followed, and the city has gone on to be judged the top city in Italy for quality of life. Jan Morris pointed out that ‘Trieste can be a bewildering city but it habitually free of hassle. You can drift through the place’ Navigating the city is made very easy by the truly excellent system of signing, with frequent ‘totems’ that explain the significance of a particular area or building. These are linked up through a series of trails with different themes, which are easy to understand, and of course linked to the internet.

The city won the title of European City of Culture in 2020, and is also very proud of its designation as a UNESCO ‘Global Centre of Learning.’ We were told by the Professor Fantoni, who leads a think tank for scientists, that in Trieste ‘people are not surprised by anything’. This makes it an excellent place for creativity. There are probably more researchers per head than anywhere where else in Italy, with some 30 research and international institutes, which makes it comparable with the Santa Fe Institute in New Mexico. Regular conferences and festivals also engage local people. This has led on to creating a modern Congress Centre in the old Port. Nearby a building has been converted into the Urban Centre, which supports start-ups and offers space for events.

Connectivity is excellent. The city is extremely dense and space is scarce. Hence one the greatest successes has been in developing an advanced bus system. A consortium for the Province has created one of the most extensive public transport systems in the country, with many routes having a bus every ten minutes, thanks to the advanced use of IT. As a result half the trips are by public transport, which includes Park and Ride sites on the edge of the city. The centre has been extensively pedestrianised with very high quality paving, with cars diverted to the edge.

The port, which moved Eastwards, is now highly successful especially in using rail to move containers. Interestingly the managing director was formerly a professor of urbanism. As well as a tram, unfortunately out of action at the present time, a cable car up to the hills is planned, which will cost £50 million.

Valorising the city’s common wealth

The city looks very prosperous now. The Council has been highly successful in making bids for funding in order to make the most of all its assets. A few years ago it took control of some 70 hectares of the old port from the Italian government. The development of the Porto Vecchio is run by a consortium between the city, the port, and a group of investors. A masterplan is guiding investment to create a mix of uses that will effectively extend the city centre by about a third. These include a new museum of the sea, the conservation of the existing buildings, including some very splendid warehouses, one of which is now a conference centre, and high quality streets with permeable surfaces. A linear park will further enhance the area. Some 40,000 people are expected to live there eventually.

Trieste is pioneering ‘open governance’ to engage citizens in what should be done with areas in new of improvement. This applies to common goods such as squares or public realm (‘bene commun’ in Italian). As well as lots of meetings, the internet is being used discover people’s views. The concept of ‘valorisation’ has no direct English equivalent, but essentially means making the most of property assets for the public as well as the private good. The beautification of the city centre will have attracted investment from business and financial institutions, which is giving the whole city a new purpose.

While open space is scarce, the city’s young children are free to learn and play in a series of Ricreataris that the city runs after school, one in every district.

While Jan Morris focussed on a sense of melancholy, it was clear from all the people we met that the city has a new sense of purpose. The atmospheric Café San Marco , which opened in 1914, may no longer be filled with dissident intellectuals, but now attracts young people with laptops as well those enjoying fine cakes with their coffee, or buying a book to read.

Conclusion

Trieste is one of a number of old port cities that have had to transform themselves. The key has been making the most of all the city’s assets, which includes of course its waterfront and a diversity of people. A distinct culture and one of the best universities in Italy helps attract and retain young people. It has also gained international recognition as an important scientific centre. The local authority has played the key role in putting together over 70 projects that have attracted grants, which in turn have mobilised private investment. A dynamic and entrepreneurial Mayor with a business background has been invaluable.

Dr Nicholas Falk

October 3rd 2022/15 November

Dear Nick A lovely postcard from Trieste With all best wishes for the festive season Georgia Professor Georgia Butina Watson Head of Department of Planning Faculty of Technology, Design and Environment Tel: 01865 483 438 Fax: 01865 483 559