Creating common wealth in lovely Ljubljana

How can a small country flourish in today’s highly global economy? Experiencing the delights of one of Europe’s smallest and newest countries, made me reflect on the nature of capitalism in the 21st century when intelligence could be driving a fourth industrial revolution. Slovenia has gone through subservience to Venice in the Middle Ages, then 50 years as part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, before emerging as part of the state of Yugoslavia after the First World War, with its own language, and the architect Joze Plecnik who helped beautify the historic core of Ljubljana. After the Second World War, Soviet-style system-built apartments predominated, but after Yugoslavia dissolved in the early 1990s, a programme of beautification began again. Today, the centre is traffic free, clean, and has a quality that matches the very best European cities, such as Vienna and Copenhagen, with a population of only 300,000 in a country of 2 million.

The historic core has fine architecture (left), the museum houses the oldest wheel but also an exhibition on work (top right) and local architect Jose Plecnik celebrated the river (bottom right).

The explanation for Slovenia’s success cannot just be tourism, with only 42 km of coastline! True it has one of the most atmospheric of seaside towns in Piran, and a busy resort in neighbouring Portorose, but these are dwarfed by the towns along the Adriatic coast in neighbouring Croatia. It does have the enterprising port in Koper that seeks to rival Rotterdam in cargo handling, with a fine new motorway that extends through to Vienna and beyond. But though connectivity is a necessary condition for growth, you need much more to combat the brain drain that afflicts smaller countries. So could the explanation lie in how Slovenia has stimulated enterprise while avoiding some of the dangers of market capitalism, which values the individual over the collective? A city with no visible beggars or litter, and a dynamic Municipality competing for the award of the Academy of Urbanism’s Great European City, seems to suggest there is another way.

The seaside town of Piran (left), and attractive squares set into the hills (right)

Natural capital

The dominant feature of the landscape is wooded hills. Some 70% of the capital is covered by forests that help cool and clean the air in Summer, while in Winter as many as 40% ski. The water is so fresh it does not have to be treated. The Slovenian word for ‘clean’ is Snaga, which is the name of the municipally owned waste department. This has achieved one of the highest recycling rates in Europe thanks to investment in advanced facilities for sorting and processing that handle 110,000 tons of rubbish a year. Not surprisingly Ljubljana was voted European Green Capital in 2016.

Above: SNAGA waste centre

Instead of an arid green belt, the woods come right into the town, creating fine parks with superb restaurants and picnic spots. The river has been opened up and new bridges built to make natural meeting points. The old buildings have been sensitively restored and reused, and investment in the public realm has boosted the many bars and restaurants and speciality shops and galleries that make the centre so special.

The streets are highly walkable with ample places to eat and drink

The greatest achievement has been taming the car, which means the centre is quiet and pollution free. When the Mayor Zoran Jankovic was first elected he saw the biggest problem as traffic. Since 2008 traffic has been excluded from all the main streets in the centre, creating some ten hectares of pedestrianised streets. With 26 Park and Ride sites on the edges, and a superb municipally owned transport system, behaviour has been radically changed, and the city now boasts one of the highest cycling rates. Interestingly originally only 50% wanted to exclude the cars but now 90% are looking to also keep buses out.

So though car ownership levels are relatively high, and a gigantic business and retail park has been developed out of an old area of warehouses, the centre is able to compete on the quality of the experience, and there are no empty shops.

Today the city is pioneering electric taxis and run-arounds.

Economic capital

Being small, makes it all the more important to tap knowledge to create good jobs that will stem migration. High density apartment blocks and good public transport makes interaction much easier. The policy has been one of social mix, but 80% of households own their own property following independence. The Urbana card is like London’s Oyster Card except you can use it for much more, and the bus fares are only 1.20 euros for a 20 minute ride. As buses generally have priority, and with bus gates at the edges, car use within the centre has been kept down.

As the head of their Technology Park put it ‘We are small and so we have to be innovative to survive.’ With 55,000 students, the University is an important force, and English is widely spoken. However the City and the Regional Development Agency that covers the wider conurbation have gone much further. The Technology Park combines workspace for start-up with training, and the City put in land as its contribution. Accelerators then offer access to venture capital. An annual competition and road show flushes out new ideas. It is now the largest innovation centre in South Eastern Europe with some 300 companies and 1,500 employees, and one of the most successful of 400 world Science and Technology Parks, now with offices in India, China and Iran.

The technology park supports and stimulates start-ups (left)

Ljubljana is an important service centre, and no doubt the lively evening economy provides plenty of jobs for young people in what is a relatively safe environment. But additional efforts are going into the ‘creative economy’, with, for example, a ‘library of things’. The aim is to get visitors to stay an extra day by offering more to see and do. What is most impressive is the business-like way planning is done, with a focus on projects and their completion, rather than policies. Their slogan is:

‘Vision without action is merely a dream; action without vision just passes the time; vision with action can change the world’.

Much of the credit is given by everyone to the Mayor. Formerly the CEO of the country’s largest supermarket group, he brought a different approach to local government, and has been re-elected three more times. He sees the city as ‘all one family’, and is a believer in ‘management by walking around’. If he spots a problem he is on the phone to demand action, and for example came up with a solution to the flooding problem after four hours of walking along the river. His watchwords are ‘Just do it’. With a business background he knows how to negotiate and how to undertake public private partnerships, but he gives much of the credit to the superb team he has built up.

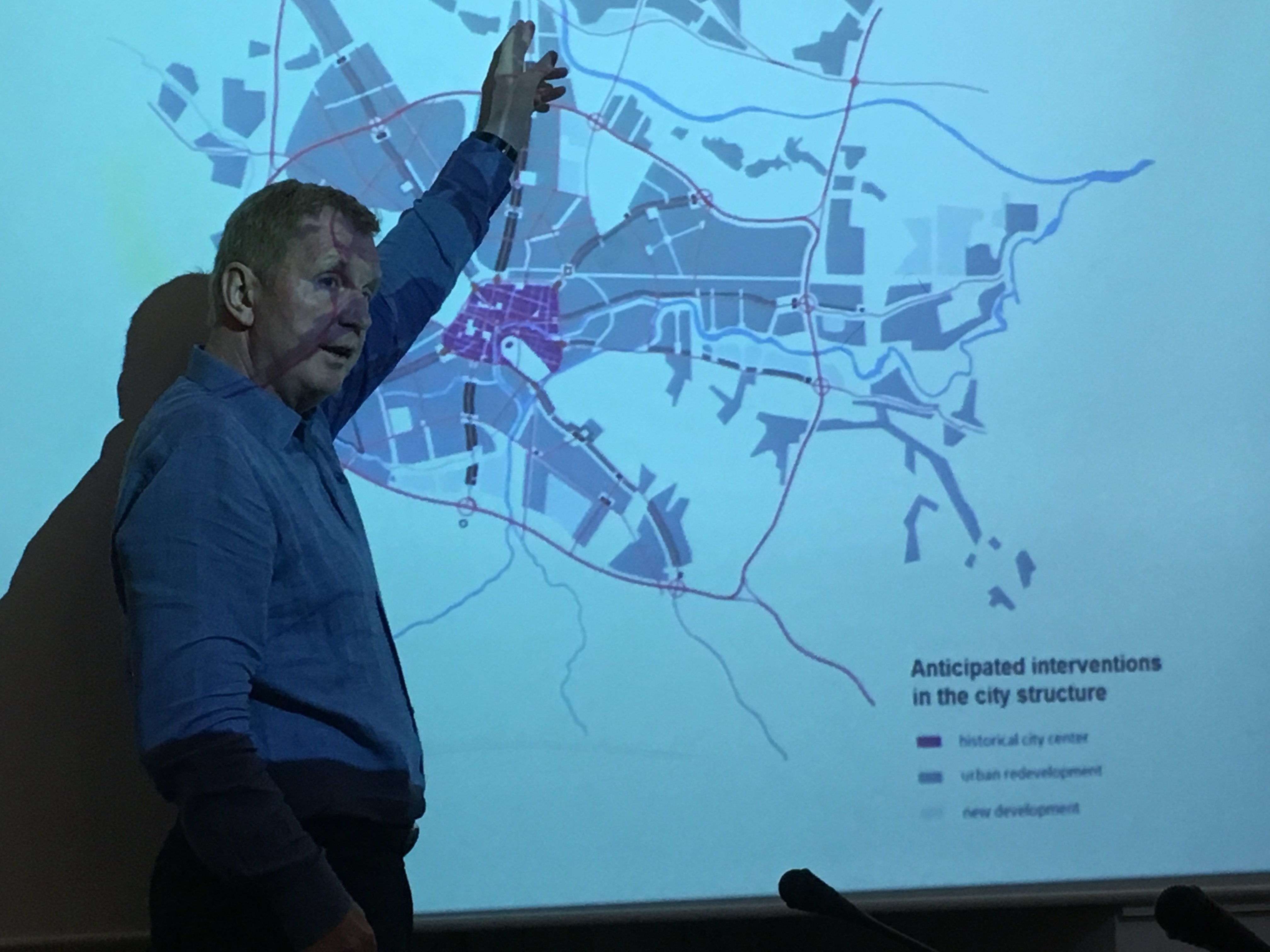

The current Mayor freed the city from cars

Social capital

Whereas ‘market capitalism’ is very much about consumer choice and buying where it is cheapest, what might be called social or human capitalism is about making the most of human potential. Egalitarianism prevails along with a friendly and informal approach to how things are run. The message can clearly be seen in the exhibition in the City museum on how industrialism has evolved in Yugoslavia, which was the pioneer of ‘workers’ self-management’ under President Tito.

The respect for other people can be seen in the cleanliness of the streets, and the pleasure people get from eating good fresh locally sourced food and drinking the excellent local wines. People living at high densities have to get on with each other, and this may be helped by the relatively low level of immigrants, perhaps 15% of the population were born elsewhere. However there is a danger that schemes that win architectural competitions, and that are then occupied by young families, could suffer from neglect over time. Also the apartment owners may not be able to cope with the costs of maintenance over time, while the social housing we saw appeared to neglect the public realm.

With a stress on ensuring that each neighbourhood has some cultural facilities, such as a library or community centre, and a delight in poetry, popular culture prevails. Indeed there are eight major dialect groups, so no wonder the use of English is so widespread! When asked to explain Slovenia’s success, the head of planning Miran Gajsek told me it was ‘Austrian hard work combined with Mediterranean improvisation.’

Miran explaining the city’s plans.

Conclusion

Slovenia clearly is ‘beloved’ by its people, and deserves to be much better known. What strikes me is not just that ‘small is beautiful’ but also that is can be extremely successful in economic, social and environmental terms. Reflecting on Vienna in Austria and Aarhus in Denmark made me see the value of losing an empire, and gaining a national or regional identity. It also showed the importance of municipalities with Mayors who can make things happen, not just beg to government for resources. The payoff comes in harnessing the intelligence and energy of young people through productive work, a message we could well do to learn.

‘Austrian hard work combined with Mediterranean improvisation.’ is brilliant.

But few countries have such beneficial geography. Somehow, I can’t see Montenegro (another small ex-Yougslav country) claiming ‘Serbian ambition with Albanian pragmatism’ would have quite the same ring. But it seems there is much to be learned here.

Apart from tourism and start ups, what are the main drivers of the economy? Is it the port? Or perhaps forestry?