Transforming Megacities

A week in China as guest of the Bluetown/Greentown Group provided an exceptional opportunity to reflect on why China has been so successful in recent years and where its cities are going. Commissioned to give a presentation on Smart New Towns to a conference of 300 of the Group’s 20,000 employees enabled me to review the features of leading ‘Technopoles’, and the impact that ‘Smart’ or digital technologies are having. Better still, it made it possible to see first-hand the amazing achievements of Chinese urban development, with a hundred cities of more than a million population, as well as the huge challenges they will face in the highly competitive global economy.

Planning with Chinese characteristics

My visit coincided with the concluding sessions of the Chinese Communist Party Congress, where hundreds of black suited men, and a sprinkling of more colourful looking women, listened to President Xi Jinping call for greater centralisation in order to tackle corruption and promote the wellbeing of the ‘people’. Rapid growth has been made possible by public investment in large scale infrastructure and the heavy industry that supports it. At the same time, private business was liberated to trade with the West, as the internet and the container opened up a global supply chain.

Millions of rural peasants have moved into cities on a temporary basis to work in the large factories that supply the West with consumer electronics and much else. 43% of the population are said to be employed in manufacturing compared with under 20% in the West. Many of the factories are located along the Eastern seaboard, fuelling the growth of cities such as Shanghai, the old trading centre, and Hangzhou, known as the headquarters of Alibaba – the Chinese version of Amazon – as well as the great West Lake. Between them stretches a seemingly endless urban sprawl of isolated housing and small farms, and then great developments of towers as far as the eye can see.

The Bluetown/Greentown Group has exciting plans (left), Hangzhou is built around a vast lake (top right) a Bluetown/Greentown agricultural research centre in the city (bottom right)

As the superb International Planning Exhibition in Shanghai’s People Park brings out, China is facing up to the new challenges. The urban area is now almost wholly developed, thanks to policies for increasing living space and replacing the old crowded lands. Shanghai metropolitan area now has a population of over 24 million making it the largest city in the world, equal in population to the whole of Scandinavia, and at densities many times that of Central London. The former marshy area in Pudong, across the vast river from the famous Bund, is now a dynamic business district. Chinese planning policies zone areas for distinct activities, and do not encourage mixed use.

Shanghai is lit up by night (left), Shanghai is vast: this section of the model in the Shanghai International Exhibition shows the area around the high-speed rail station (top right), cities are looking forwards (middle right), the Bund is a major attraction (bottom right).

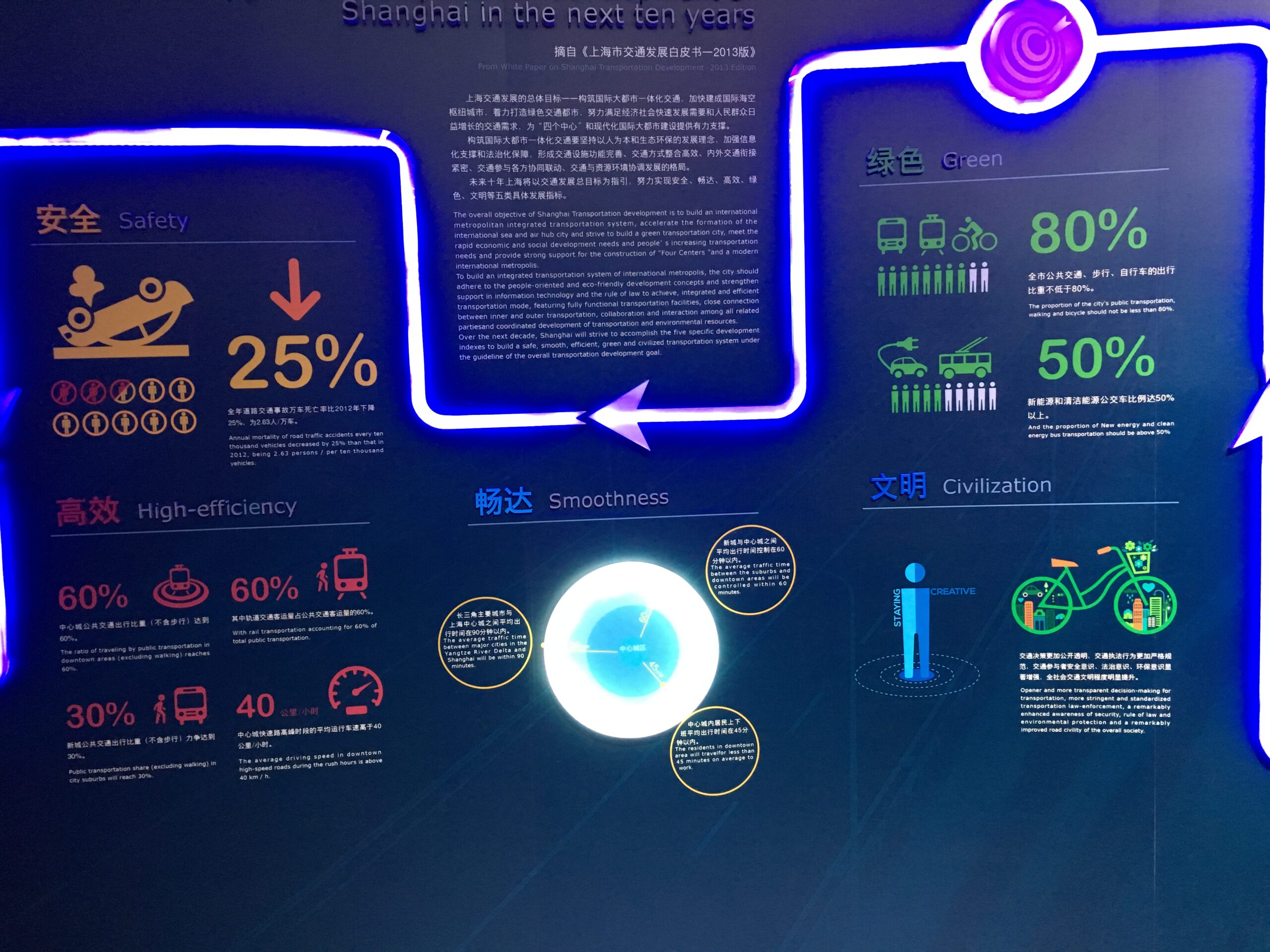

Having provided the advanced infrastructure to connect cities with high speed trains that, for example bring Hangzhou within an hour of Shanghai compared with three hours by motorway; the priorities are shifting to improving the quality of life for city dwellers. Pollution blots the skyline. Endless traffic brings congestion and stress despite the many lanes of motorways. The suburbs appear mostly faceless and lacking in amenities. So targets have been set for cutting local journey times, and recently built metro systems are being extended. Yellow hire bikes litter the pavements. There is a national policy for creating 1000 planned new towns each with a distinct ‘character.’ Interesting experiments are being made in promoting energy efficient ‘eco-towns’. But agricultural land, like the UK Greenbelts, is sacred, and so development has to be concentrated on formerly used land, which in practice means the demolition of traditional housing and its replacement by high rise blocks of apartments.

Much of the new housing looks the same (left), communications between cities by rail are rapid (top right), cyclists and motorcyclists check their phones at a junction (bottom right)

Chinese business models

What fuels such rapid growth, and makes it possible for Chinese companies to take over whole markets, is the exceptional relationship between the state and private business. The state owns all the land and the main utilities. Local authorities have no source of income other than selling off 70 year leases to developers. Agricultural workers have to be rehoused, and can enter into collective agreements. As in the UK, locations with good access, for example through proximity to new government funded metro lines, will fetch the highest prices.

Housing design seems to have gone through fashions. Of course in China as a whole urban areas are at many different stages, but as in the West, there seems to be a shift back from suburbanisation to reurbanisation, as the young and best-educated favour the amenities only found in cities. But rapid growth has produced standardisation, and a mass society used to order. China is therefore committed to looking at what works best elsewhere, hence our conference. As we were told by the company’s President at the end of our conference, the policy is one of ‘Learning and Practice’. China is keen to recognise mistakes and change direction where needed, and there is a welcome spirit of optimism and pride.

Examples of innovation we saw were the new town where we stayed – Peach Blossom Valley – where a whole neighbourhood of houses has been built along traditional Chinese courtyard lines. The single storey housing units take up 100sq. metres and a similar area is given over to the delightful gardens, which encourage a contemplative spirit. Security is stressed. At the heart of the town are several streets of shops, and further away, we were shown round an innovative new primary school where Montessori classes are taught which allow children to learn at their own pace. This curvaceous two storey building adjoins housing for the elderly with the aim of integrating the two worlds. The whole complex is traffic free with electric buses that can readily be summoned.

New traditional looking housing in Peach Blossom Valley, Hangzhou has many appeals

Beautiful landscaping were also features of an agricultural research centre and a small village designed to attract tourists. The idea one suspects is to convince the authorities by the quality of the design to allow the development of housing on agricultural land. This would make the project commercially viable, as otherwise it is hard to see how the enterprises can ever cover their costs other than as a demonstration of the company’s commitment to creating better places. It seems that the system works because the largest companies have good access to finance, and also no doubt political connections. BlueTown/Greentown Group has sent a number of parties to study good practice in the UK and are now proposing to visit other parts of Europe in their quest to be ahead of the market.

New and old worlds

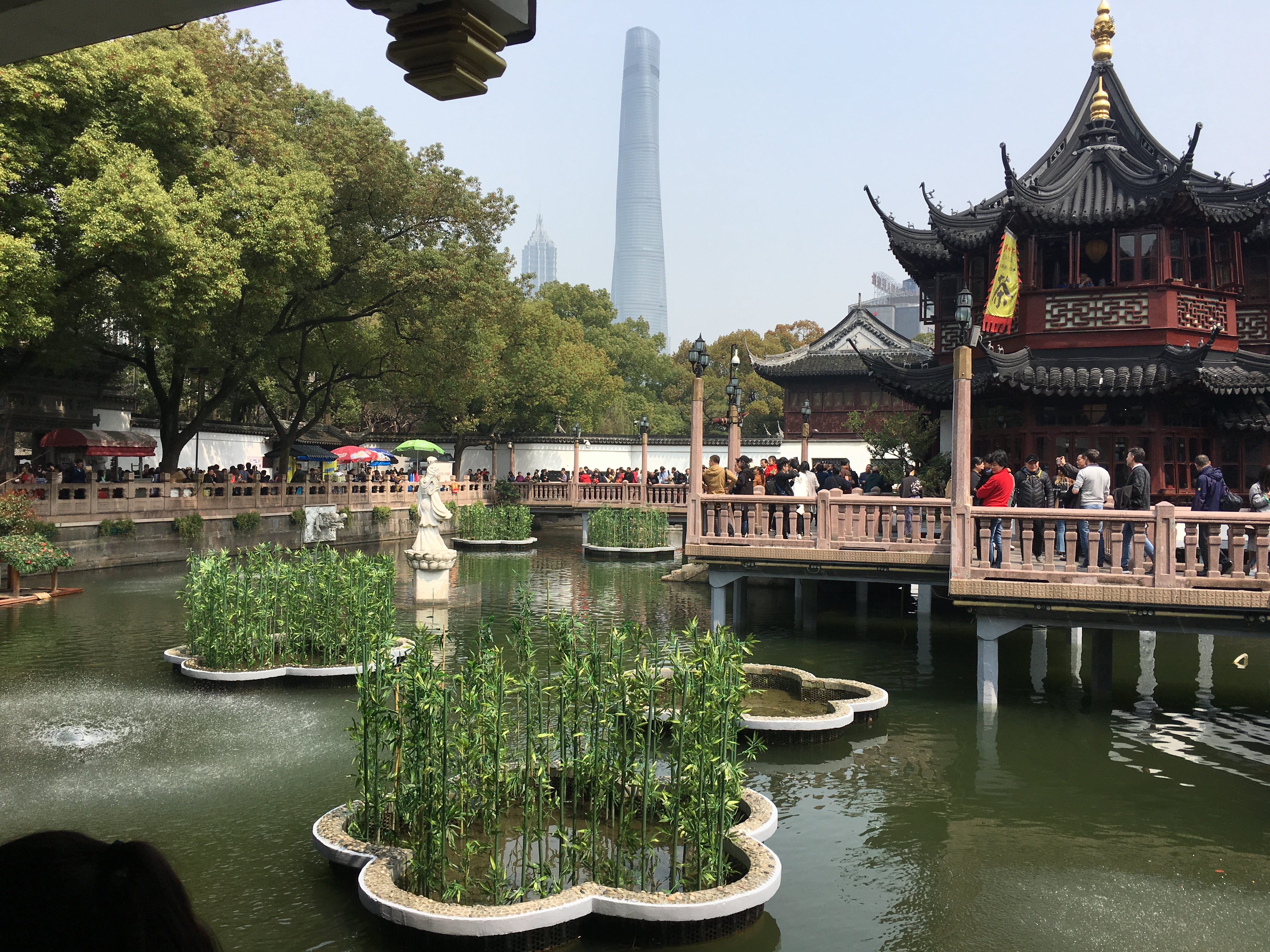

Walking through the main centre of Shanghai provided the chance to observe the changes that are taking place. Former warehouses in the old French Concession have been turned into lively bars and eating places. The two principal streets leading to the river have become the smartest shopping streets. We enjoyed a Chinese meal with former URBED intern Jie Lu in an atmospheric restaurant carved out of the third floor of a modern shopping mall. As we walked afterwards, we were struck by the exciting lighting effects, but also by large areas that were clearly destined to be the next big redevelopment scheme. The Bund itself, with its magnificent bank buildings, is now the major tourist attraction, with a raised embankment along the river looking over fleets of river boats. Nearby signs to the ‘Old City’ bring one into a replica of an old neighbourhood, with lots of shops but also a splendid ancient walled park with masses of ornamental buildings overlooking water features.

Landscaping is done very well

Yet close by these managed attractions lie large areas of ‘lanes’, where families are still crowded alongside the small businesses that they run. To me the juxtaposition of old and new was the most interesting part of the city, as the modern offices could be anywhere. Yet the boarded-up windows of many buildings suggested they were doomed, and the idea of adaptive reuse’ has not yet taken hold as it has in most Western cities. The contrast between old and new could also be seen in manning levels. While factories achieve the highest levels of productivity with modern machinery and compliant labour, the service sector looks very over-manned. Large numbers of people doing any task are perhaps the way China keeps its massive population employed.

The French Concession, Shanghai (top left), the ‘lanes’, although crowded, host rich inter-generational communities (bottom left), new tower blocks are replacing the old ‘lanes’ (right)

Order has also achieved by people taking out loans to buy leases on flats or to help their children get a better education. The one child policy has created a demographic time bomb. Without siblings or many relations, there is strong pressure to work hard and to consume, but people retire relatively young. There is a reverence for authority from Confucius onwards. This perhaps makes it harder to see the opportunities for conserving and improving ordinary places before they are all lost. Yet as basic housing markets get saturated, it is probably easier for entrepreneurial Chinese businesses to transfer ideas they have picked up on foreign visits, and make a go of them. If they do not change the product mix to favour more streets and neighbourhoods, and cities become over-dependant on ‘immigrants’ from the countryside, the situation could become as explosive as in many Western cities.

Small businesses are common (top left), many people work to provide services (bottom left), drying clothes hang across the Lanes (right)

Changing direction

In mulling over what I learned from my brief visit and enquiries but also wide reading (including an excellent new book on China’s Urban Revolution by Austin Williams), I feared for the impacts of a downturn, especially given Trump’s stated policy of cutting the US trade deficit with China. arge areas of lookalike tower blocks could experience a fall in demand when better alteranives a built,, and neighbourhoods are restructured as happened in the UK. It is also likely that if companies stop hiring, there will be thousands of dissatisfied young people who have played by the rules, and feel cheated unless other career optkons are opened up . In my presentation, I suggested that China could learn a lot from the rise, fall, and subsequent resurgence of central Manchester (and indeed other post-industrial cities). . However, this will require many more two way discussions, rather than relying on presentations alone.

If both our countries face similar challenges in adapting our cities and rural areas to new economic roles whilst living within environmental constraints, there is surely scope for collaboration at many levels. It may actually be easier to apply the kinds of principles URBED has been advocating for years, especially as Ebenezer Howard’s Cities for Tomorrow is still treated with a reverence it long ago lost in the UK. The challenge in both countries is not just to draw up attractive masterplans but to set up the mechanisms for financing and implementing new settlements that will stand the test of time. This above all means devising better ways of resourcing local government. Given the many Chinese academics in leading British universities such as Cambridge and UCL, a good place to start could be to rethink the relationships between town and country in the light of demographic changes.

People enjoy their caged birds in a park in Shangai

Thanks, Nick. Truly, a land of opportunity.