Turning a sleepy town into a great French city

Revisiting Montpellier in South East France after almost 20 years offered a unique chance to assess progress in the fastest growing city in France – which has gone from 28th to 8th in size in just a few decades. I met up with the people running the City in the company of members of the Academy of Urbanism, who were assessing it for the Great European City award. The two day visit provided exceptional insights into what makes a great city, as well as how to make the most of any assets. Montpellier as well as any European city shows what good urbanism can achieve.

Of course Montpellier starts with some advantages over cities in Northern Europe. It is in the sunny South of France and now less than three hours from Paris by TGV, but with strong competition from larger cities such as Nice. It had one of the oldest universities in Europe, with some 70,000 students out of a population of around 270,000. These helped attract some of the most advanced firms in France, and become a magnet for young people, thanks to municipal leadership and financial ingenuity.

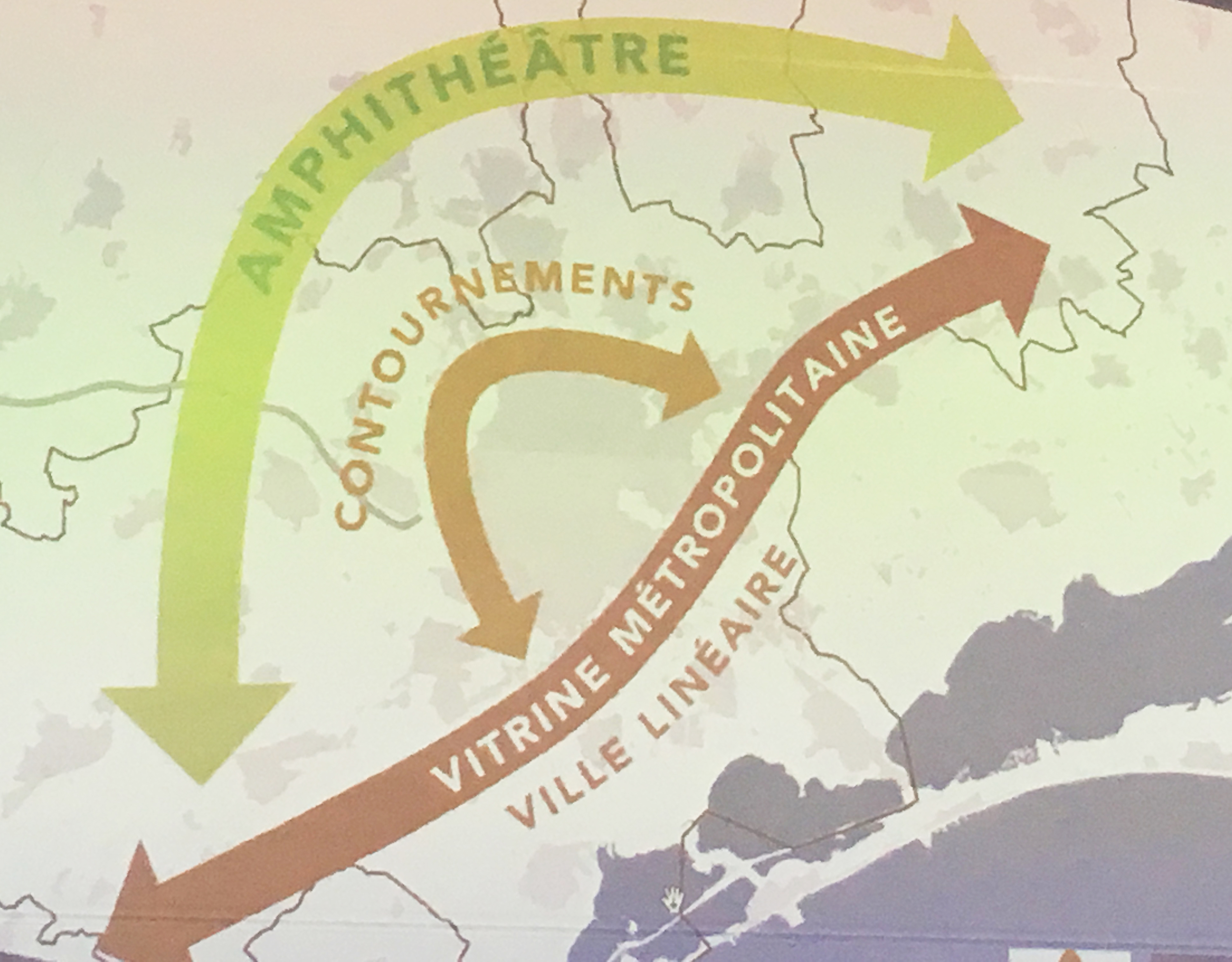

A grand spatial plan

The City was little known outside France before a law professor called George Freche took over as Mayor, a position he went on to hold for almost 40 years (1977-2010). A start had been made under President De Gaulle, who provided some funds to house former colonists from North Africa, and to promote tourism in the curiously shaped La Motte. But it was Freche who had the courage to promote cultural events in 1977, to take over military land in the historic city, and start expanding the historic centre.

He commissioned the Catalan architect Ricardo Bofill to design and then build the ambitious Antigone quarter, a pseudo classical response to the 70s Polygone shopping centre. This provided 4,400 new homes on 45 hectares, 25% of which were public housing, and was a ‘laboratory’ for new ideas. Technoclusters from 1985 made the most of ‘grey matter’ or brain power, with five clusters each with their own conference centre and governance.

Freche had a simple but grand spatial vision of reconnecting the city with the Mediterranean on which its early fortunes as a trading town had been based. The cohesive spatial plan known as SCOT is unusual in defining the areas not to be developed. The land where Porte Marianne is built, which covers some 400 hectares, had been mosquito invested swamps, and so the first step was to make space for the River Lez, which forms the spine of the new city. A development framework divided the land into four quarters, each planned by a different architect, and marketed for a mix of uses and tenures to create more balanced communities than are usually found. At least a third was kept as open space, with a high level of biodiversity. There is an Eco Quartier with 2,000 new homes and 5,000 residents as well as new offices and a seven hectare park which provides a buffer zone with the water.

Funds were mobilised to build the longest tram line in France, and now the most successful. This has been followed by three other lines, with line 3 running out almost to the sea. Though congestion around the old town can be high, the trams enabled traffic to be removed from the centre in 1986, as trams and pedestrians can happily coexist. The tram also helps to orientate the visitor, and the line just completed circles the town on the line of the old walls. The City has also pursued sustainability by investing in a large Combined Heat and Power complex which provides heat to all the new buildings, using biomass. The Town Hall by Jean Nouvel was opened in 2011, and is also designed to minimise energy consumption.

The city suffers from high unemployment among young people, which has doubled since I was last there. Some 30% of the population is Muslim. The city feels welcoming, and there was none of the graffiti which had struck me twenty years ago. In truth, historic and university cities inevitably tend to attract more people than can find jobs. The challenge is how to grow them in ways that minimise sprawl and social exclusion. The achievement in mixing social with private housing, and some 40% of housing in Antigone is social, must have helped Montpellier avoid the riots that have beset other French cities.

City development company

Montpellier has built on a huge scale, over 2,500 new homes a year, and at one time over half the population was involved in construction. The key has been assembling the land and ploughing most of the uplift in land values back into infrastructure. Development was promoted by a private company called SERM owned largely by the municipality. The Caisse des Depots, the state investment bank, took a 15% share, and as they scrutinise investments carefully, this helped in attracting finance from commercial banks. Private developers we met were quite happy with the role played by the municipality, as risks had been reduced, and funds were raised at lower cost than they would have had to pay.

SERM employs a staff of some 120, of whom a fifth work for the energy subsidiary. Their work is focussed around a series of ZACs (Zones d’ Amenagement Concerte) where extra powers are available to acquire land if required. The City has been assembling land for 30 years, which puts it in a powerful position as far as securing quality is concerned. Serviced sites are now much smaller than they used to be. As an example part of the area around the recently refurbished railway station has been the subject of competitions for a 0.4 ha site. Architects and planners in the municipality had drawn up the brief, in terms of uses and massing, and then architects were invited to come up with schemes, for which they were reimbursed. The land is then sold to a developer at a prearranged price, and the winning architect(s) have to be taken on. Work started in 2008 and the first building was completed in 2016. The scheme looks extremely attractive, and has benefitted from the procurement process.

Housing choice is assured by requiring a mix in every scheme, with around a third market sale, a third are affordable and sold at a discount with requirements for repayment when resold, and a third are social and rented by the City or one of the housing associations (HLM) active in the city. The high rate of building and variety of new homes has taken some of the pressure off housing in the historic centre. Generous welfare policies help reduce the problem of homelessness to manageable proportions. Though there is little activity by self-builders or cooperatives, it is much easier to obtain a plot than in the UK, and the new developments include detached housing as well as blocks of apartments.

The City has been very successful in attracting new businesses to set up in various incubators, some making use of old buildings. Montpellier is said to have the world’s best incubator. 40,000 new jobs were created in the decade after 1995. It has been a leader in the development of Technopoles or science parks connected with research and innovation in the universities, and over 14 business parks were set up early on. In addition, as the population has grown, it has generated demand for services of every kind, and the city of Montpellier provides over 70% of the jobs in the Metropole. As French local authorities can raise much more of their budget from the local population growth is self-reinforcing.

Integrated local transport

One of the main achievements has been the network of stylish trams, which promote the image of a progressive city. Funded through a combination of national, regional and local sources, a great incentive has been the Versement Transport, a charge on the payroll of firms employing more than 10 people. Though fares are low, about a euro a trip, the farebox almost covers the running cost, and the first line, which is 10km long, is the most successful in France. 75% of its 350 million euro cost was raised by the District. As the head of the Tram system explained at a Sintropher conference, running trams economises on labour as one driver can handle some 300 passengers at peak times. The city’s research shows that even in the out-of-town shopping centre of Odysseum, some 40% of purchases were made by people arriving by tram, and the out of town hypermarkets had 15% of customers on public transport. Today new developments have to be located on the tram system, and the adage is ‘No trams no business’. The Municipality is now doing away with roundabouts to help pedestrians cross the street.

Though the cost of installing trams can seem high, half the cost goes in redesigning and rebuilding the roads. Cars were taken out of the centre, and some 14,000 car parking spaces are provided in a series of underground car parks. Recent research has shown that car usage has been cut to 40% of trips, and residents in the centre no longer need cars. The next stages will be to provide High Performance Buses to serve the more peripheral employment areas. A new station on the TGV network is being built on the edge of the city, and work is now starting to replan the wasteful car-based commercial developments on the outskirts of the city.

Effective governance

The fragmented nature of French local government, with some 33,000 communes, makes strong local leadership essential. This has only been possible since President Mitterand devolved power from Paris to the regional cities, and unleashed the growth of provincial France in the 1980s. The City of Montpellier, with its population of 270,000 since 2014 forms part of a Metropole or agglomeration of around 430,000 and there is a population of over a million in the wider region formerly known as Languedoc, of which 43% are under 30. Development is secured through the city owned development agency SERM, who is usually chosen to lead developments in each of the ZACs.

The Mayor of the City is also President of the Metropole, which brings in 31 different municipalities. George Freche and his supporting team were famous as enjoying being a ‘big fish in a small pond’. The current Mayor, Philippe Saurel, had been his deputy. Saurel stood with his ‘list’ of associates as an independent, on the ‘ticket’ Montpellier est vous. This enables him to appeal to people from all sides. Interestingly he is a dental surgeon by profession, and is promoting his own unique brand of city leadership under the theme of Repairing the Republic.

Saurel is organising a network of Mayors in other Mediterranean cities, such as Palermo, with the ultimate aim of creating a new ‘parliament’ of Mayors or Parliamente de Territoire, with some 55 conurbations. The city already employs over 4,000, and will be merging with the Metropole to employ some 6,000 staff. This gives it a huge influence, and the continuity is noticeable, which must help in delivering the ambitious aims that have been set for the City.

Thanks Nick: great note and very readable. Best Regards David

Sent from my iPhone

>

As ever, Nick, very useful and inspiring. Growth from 28th to 8th largest city is the equivalent to Luton becoming the size of Leeds. The only UK town which gets close is Milton Keynes.

Greatly approve to the method of procuring buildings by architectural competition and then tendering them to developers.

Do we know of any pubication that documents Mitterand’s devolution of power to the regions and the subsequent explosion of the provincial cities? It would be good to compare it with the UK’s current devolution deals.

Thanks once again for the inspiration.