HOW TO PROMOTE QUALITY HOUSING

A tour around major developments in Cambridge’s Southern Fringe provided the prelude to a lively discussion on promoting quality housing. The event held in the new primary school at Trumpington Meadows was part of URBED’s 40th anniversary celebrations, revisiting key pieces of work that we have done over that time. In Cambridge it was an opportunity to assess the impact of the Quality Charter that we produced for Cambridgeshire Horizons in 2008. The developments that we saw on the tour certainly looked very different to the usual modern housing estates, and you could almost feel that you were in Holland at times, with clean modern design, high quality brickwork, and uncluttered public spaces with a lot of greenery.

Andy Sharpe, who has been running Grosvenor’s development in Trumpington from the start, pointed out that it is the public realm, not the buildings, that create the most value. The scheme is a joint venture with the Universities Superannuation Scheme (USS) and walking around people were particularly impressed by the fancy brickwork. Several hundred acres was taken out of the green belt in 2004, and a new country park created, opening up access to the countryside.

The financial crash of 2007 has delayed progress; however Grosvenor went ahead with the infrastructure, allowing them to sell the first phase of 350 units to Barratts in 2010. Several architects later, they have succeeded in creating a new neighbourhood with a lot of character and nearby residents are delighted to see how much the houses have sold for! The key to quality has been keeping control, implementing the first Design Codes, and selecting the right design team, who have an ongoing role. A further phase, if it secures approval, will see the development of a Sports Village with 500 homes, further broadening the attractions of an area on the edge of Cambridge next to the Park and Ride off the M11.

Implementing the Barker Reports

Dame Kate Barker, a former member of the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee and now on the Board of Taylor Wimpey, succinctly summed up the impact of her report on housing for the last Labour government. Many of the proposals to simplify planning had been implemented, but the important National Planning and Advisory Unit had been dropped by the incoming Coalition Government and after a brief period when we built more than 200,000 new homes a year, output has fallen back dramatically and government has not been able to ‘join things up’ and build the housing that we need. The fractured state of the planning system makes it difficult to assess what is happening nationally. However her research into Hertfordshire planning authorities found that approved plans were only meeting 75% of household projections. Responses to consultation before the plan was adopted was minimal, 188 comments in Stevenage. In another council many had the same opening paragraph!

Urban extensions (like the ones URBED promoted through their Wolfson Prize submission) are important if we are going to provide sustainable transport and build ‘places not homes’. The Green Belt is however a barrier to this type of development and no longer plays a useful role in stopping the coalescence of settlements. Interestingly the green belt was originally invented by Elizabeth 1st to prevent building more than three miles away from Westminster, which would have stopped London ever becoming a leading capital city. While the green belt does still perform a useful role, we do not need 13% of England to be devoted to it. Instead we need to find ways of collaborating across boundaries and with different stakeholders to increase housing production. So Cambridge is an important model in this respect, and a place where she personally would like to live.

Learning from Europe

Marc Vlessing, founder and CE of Pocket Homes, argued that we could only satisfy the demand for affordable homes by building very differently and drew inspiration from the Cambridgeshire Quality Charter for Growth that had been greatly influenced experience in Europe, particularly the Netherlands. Pocket Homes caters for a young market where 50% of those under 30 cannot afford to invest more than £220,000. Meeting this need requires innovation but this is very difficult in the UK, as evidenced by the time it took to start building student and retirement housing. Sir Peter Hall told him that the planning system in the Netherlands is like the British, it is just that ‘they see plans through’.

Doubling output while securing quality requires intermediate agencies to assemble the land and provide the infrastructure, and make development much easier. We need to support SME’s to break the dominance of the five volume house builders, who are now responsible for half our housing output whereas they once built less than a fifth. This means using public land strategically rather than selling it off to the highest bidder. But he was cautiously optimistic that we are now starting to make progress.

Establishing Quality Standards

The Quality Charter for Growth, which URBED developed ten years ago through a series of study tours to exemplary schemes, seems to have had a very positive influence, judging by the general reactions. The Chair of the Quality Review Panel, Robin Nicholson, regretted that there was no longer funding for research. The Panel includes a range of professional disciplines and uses the 4Cs that at the heart of the charter –Community, Connectivity, Climate proofing, and Character –which he thought were ‘wonderful’. They have had 85 presentations in five years and act as a ‘critical friend’ to developers. His presentation prompted a useful discussion on some tricky issues:

Community Facilities are needed from the start of a scheme and a school is fundamental as the ‘community hub’ in the early days. Jo Mills pointed out that in Northstowe they are now putting the local centre on the edge, based on what they learned through the Sustainable Urban Neighbourhood Network that URBED ran for JRF. The delays have produced a change of heart on the part of local people who now look forward to using the facilities of the New Town. But even when housing is designed to be ‘tenure blind’, there have been problems in bringing together different classes, as for example not everyone wants to shop in Waitrose!

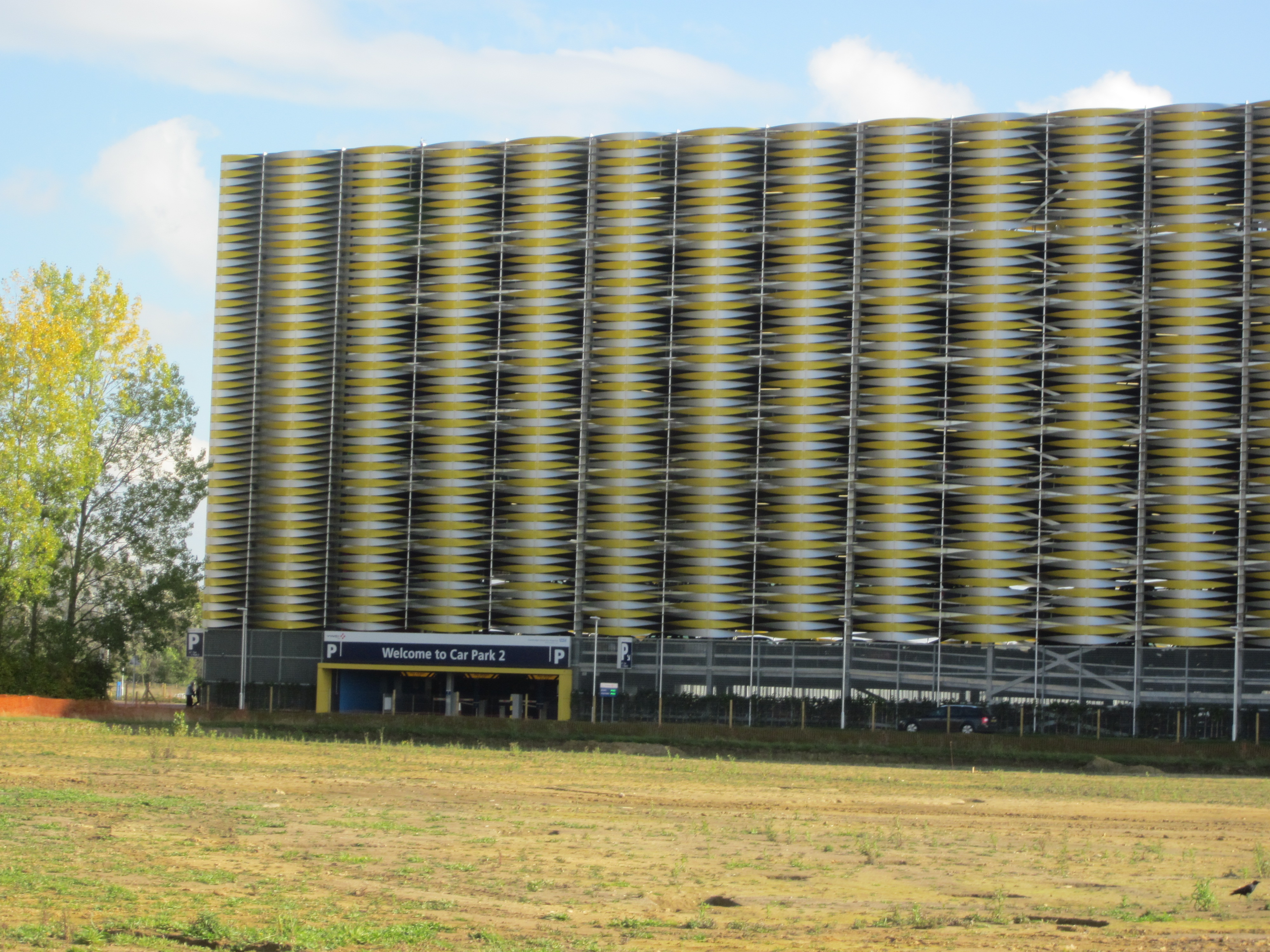

Connectivity: The Guided Busway is proving very popular out to St Ives, but was said to be underused from Trumpington to the Station. This could be because it is scarcely promoted and hard to find, as several visitors noted. Cars may increasingly be seen as ‘unwelcome visitors’, but as people increasingly work on the fringes of a city or in other towns, cars do play a crucial role, and do require adequate parking. Visitors liked the way the schemes seemed to favour those on foot or bike, but it was still difficult to prevent people parking all over the place.

Climate proofing: All the new buildings are designed to be much more efficient in the use of energy. Air quality is a problem in many cities, with over-heating becoming a problem as temperatures rise. It turns out that the fine chimneys on many of the houses in Trumpington Meadows are for appearance only. The solar panels are not enough to create any Passive Houses, and few have invested in the more expensive options available. Further innovation may well be forced on developers in future by economic factors, such as the cost of traditional building methods.

Character Great effort has gone into using first-class architects, who have drawn on local features to create places that are truly distinctive. Their success is reflected in the popularity of the new housing. But there is a danger of cheapening the details after planning permission is given. This makes it essential not only for landowners to exercise stewardship, but also to undertake post-occupancy research.

Conclusion

Cambridge is rightly being praised as a model for collaboration between stakeholders. The most important message, perhaps, was that local politicians need to provide leadership and convince their electors to support something different. Study tours can play a valuable role in giving them the necessary ambition and role models to follow. Greater flexibility is also helpful in boosting cash flow, and responding to changing levels of demand. But there is still a long way to go in applying all the principles of the Quality Charter, particularly building enough homes to ensure that people do not have to spend too much time and money commuting to work. Street design could also be improved. Research into post-occupancy satisfaction should therefore be of general value in showing whether investment in higher quality pays off, and what residents value most.

Clearly Cambridge are an exemplar local authority. Their model for delivery clearly works, so we should be pushing for a Quality Charter to be a requirement for all major new developments. Perhaps the New Garden Cities Alliance can incorporate it in their work on a British Standard for Garden Cities.