MAKING STEP CHANGES

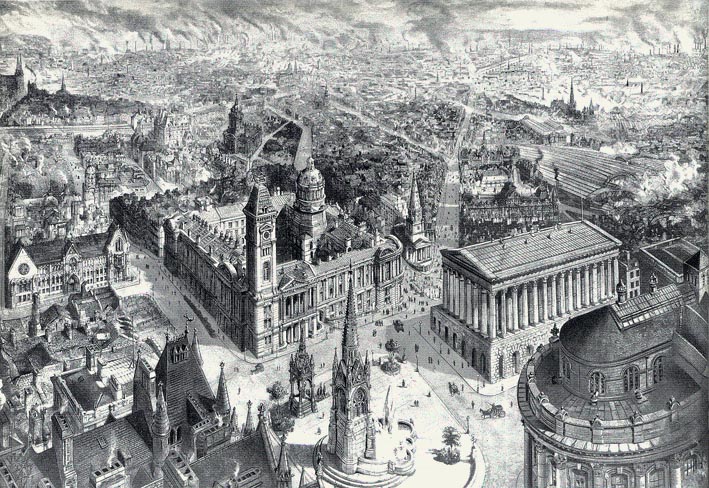

Returning to Birmingham for the Academy of Urbanism Congress, where URBED sponsored a workshop on ‘How to lose your ring road and find your city centre’, I reflected on how to achieve urban change on a major scale. A city once known as the ‘Workshop of the world’, and then dominated by the car, has become one of the most popular places for holding large meetings, revitalised the life of its city centre and generated a food culture par excellence! We generally know what we dislike about a place, and even where we want to go. But the real issue is how do you get there from here?

Urban transformation

Since 1988, when URBED helped Birmingham rethink its city centre through the Highbury Initiative, the City Council has led the way in improving urban quality and wellbeing. First came the decision to drop the ring road at crucial places to allow the city to break out of the ‘concrete collar’, as it became known, and importantly remove pedestrian subways and bring people back up into the light. Second, came high quality pedestrianisation of the links between the new Convention Centre on the canals at Brindley Place, the civic centre, and railway station. Getting the buses out of Corporation Street against the advice of the Council’s officers transformed people’s experience, and made it viable to redevelop the outdated Bullring, as a modern shopping centre, with the London department store Selfridges commissioning a truly iconic building.

The city is now attracting people back to live in the City centre, as Sir Albert Bore pointed out in his keynote speech. The process has not only conserved historic areas like the Jewellery Quarter, but also opened up new quarters, with two of the city’s universities playing a key role in both modernising an outdated campus and creating a new campus in the City Centre’s Eastside . So a city that seemed to have lost its purpose is once again the strong heart of the Midlands, and keen to see High Speed 2 with a new station alongside the original 1838 London and Birmingham Railway company station at Curzon Street. Though proud of what has been achieved, there is still a long way to go in upgrading city-wide urban quality and creating healthier places, as the City’s Medical Officer reminded the Congress. Birmingham is not yet ‘world class’, but it is on its way.

Connected city

Peter Jones, Professor of Transport at UCL, suggested that cities go through a series of phases in improving their connectivity, which really amount to ‘step changes’ as his diagram illustrated. New Street Station, and its disjointed link to the tram that goes through to Wolverhampton, currently presents the visitor with a poor first impression. It is clear that the completion of the current reincarnation of New Street Station and the on-street metro running will, in a short while match the experience of Continental cities that Birmingham competes with. Cars still intrude in some areas, but the tide is turning. Furthermore, where once the canals were ignored or avoided, they now provide peaceful routes to and through the City Centre away from the traffic, and make cycling safer too.

Charles Montgomery drew on his book Happy City to argue that frequent entrances on streets, buildings and spaces lead to people walking more slowly, and interacting more, which makes them much happier. His research suggests that small things, such as places to sit, can be equally important as grand projects. So there is still some way to go in ensuring that new buildings are not seen as individual projects and so not inward looking, but should be considered holistically, which is why urban design should lead large scale planning, and not be an afterthought.

See this diagram for the 3 stage Transport Policy Development Cycle

Ambition, Brokerage and Continuity

The overall lesson from our workshop is that regeneration or renaissance starts with a city wanting to do much better, using inspiration from other places. Undoubtedly the kind of ‘action planning’ approach pioneered in the Highbury Initiative can give city leaders confidence in achieving culture shift, breaking with past policies, and adopting new values and priorities. But nothing would happen without the leadership to broker ‘quality deals’ so that opposition is quelled, and this is where the skills of the urbanist are most relevant. People believe what they see for themselves, which is why study tours can be so valuable, backed up by supportive local media.

But regeneration takes time, and continuity counts, as the examples of politicians such as Sir Albert Bore or officers such as Sandy Taylor remind us. So while we should take inspiration from cities in many other countries, and with Charles Landry offering a stimulating range of possible models, in the end we must find ways of rebuilding local capacity. URBED’s next event in Brighton, where what we called the New England Quarter next to Brighton Station has been comprehensively redeveloped to our masterplan, will enable us to see the value of different kinds of masterplan and development framework that maintain quality while allowing for flexibility in the speed of delivery.