RE-THINKING THE MASTERPLAN

A workshop in Brighton’s New England Quarter on July 13th provided the opportunity not just to look around what has been achieved, but also to meet some old friends, such as Pooran Desai, the founder of BioRegional, and Nigel Green, who was the planning officer with whom we worked. David Rudlin explained that the New England Quarter was URBED’s first masterplan and the only one to have been built in its entirety. This was due in no small part because of the commitment of local developer Chris Gilbert of QED. The event provided a useful opportunity to assess what masterplanning can and cannot do and the lessons that can be learned from one of the few major sites in Brighton to be developed out.

Creating new public places

Pam Alexander, the last Chief Executive of the SEEDA (the South East England Development Agency) drew on her rich career for a keynote presentation to show how urban policy had evolved over the last 40 years. She is now a non-executive director of Crest Nicholson, who played a key role as developers of One Brighton with BioRegional Quintain. She described how there is increasing reliance on the private sector to promote masterplans but that they require a degree of certainty plus flexibility if they are to invest on the scale required. Yet 55% of local authorities do not even have an adopted plan, small housebuilders have largely vanished, and perhaps too much reliance is being placed on deregulation and localism. When grant funding was available, few schemes in Brighton were taken up, so what has made the New England Quarter a success?

Regenerating brownfield sites

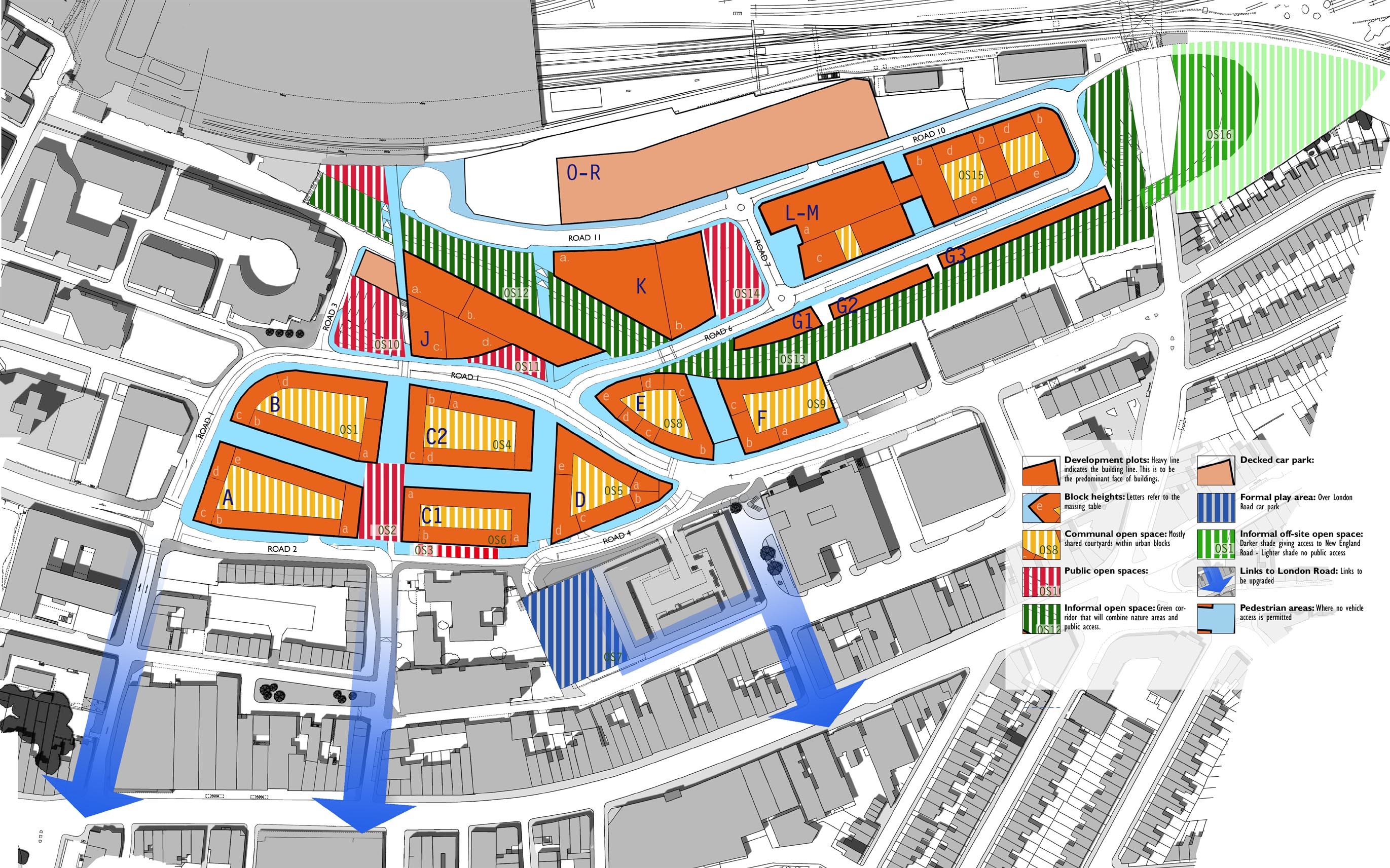

The old Brighton Goods Yard, a 16 acre site in a tightly constrained Borough, closed in the 1960’s and some five attempts to develop it had failed. The site is on a steep hill between the railway line and the London Road shopping centre. It serves as the station car park and Network Rail insisted that at least 160 parking spaces had to ve available all times as it was being developoed. It is also next to some dreary 60’s offices, but quite close to the vibrant North Laines Conservation Area. Local community group Brighton Urban Development (BUD) initially suggested URBED’s involvement based on our work on Homes for Change in Hulme and the Sustainable Urban Neighbourhood. At almost the same time, Sainsbury’s, whose scheme for a supermarket had been turned down at appeal, asked Nicholas Falk to look at some fresh proposals for putting the flats over the store. David Rudlin’s critique of the scheme led to URBED being asked to devise and eventually lead the masterplanning process (much to the consternation of the community!). Most masterplans are never built, and few have the flexibility to allow for a number of different developers. URBED’s approach drew on the way cities have traditionally evolved over time through a series of ‘rules’ that shape the different land ‘parcels’ in terms of uses, densities, and above all relationship to the street. The resulting development, which involved some ten different blocks and design teams, is remarkably like our original plan. This has not been easy and Chris Gilbert told the story of Plot J next to the station that was sold early on to generate cashflow but was then promoted as a tower by the Beetham Brothers. It is only recently that the site has been bought back by QED and the scheme on site by Hyde Housing, is much closer to the original masterplan. It will at last allow the completion of the greenway and a direct pedestrian route from London Road to the Station.

Making development viable

Chris Gilbert doubted if the scheme could be done again because food stores are not as profitable as they once were. Funding from Sainsbury’s was absolutely crucial for the infrastructure, which included a new road and a multi-storey car park before there was any return on the investment. There was concern from people in the room about the unaffordability of the housing. As Sheila Montford of the Brighton Society forcefully pointed out, the key problem for the UK is that housing is now quite unaffordable almost everywhere. This was partly due to ‘buy to let’ investors outbidding owner occupiers, while there is no longer funding for social housing. No national developer would have spent the time engaging with the local community, who were very hostile, or ensuring that the many construction problems were overcome. Bio Regional’s original involvement was also at the behest of the community and led to them being given an ‘informal option’ on one of the plots allowing the most innovative part of the development to go ahead. The ‘patient’ approach shown by the original land owners, Network Rail, also helped, once trust had been built up. It was interesting how pressure from the community had forced the developers to be more innovative than they would otherwise have been but they have since become converts going on to produce some of the first low-cost housing made from containers in Brighton. Planning started in 1998, consent was granted in in 2003 and construction started soon after. Costs such as £800,000 for diverting 150 metres of fibre optic cable bring out some of the problems of redeveloping brownfield sites.

Engaging the local community

Articulate local people were strongly opposed to the scheme largely because of the Sainsburys. Their feeling was that they should be able to determine the use of the site and came up with several hundred ideas for what should go on the site. In fact many of their proposals were eventually incorporated into the scheme but it was regrettable how bad-tempered discussions became. Nigel Green explained how the Council set up a working group of eleven stakeholders to produce a brief, which led to further objections, but did enable the Council to adopt a brief to which the masterplan responded. A University of Westminster study found that development in the UK was much harder than in the rest of Europe due to the power of local groups and the adversarial nature of development. Questions were asked about the community that now lived on the site. Because of the language school there are many students living on the site. Perhaps too much time was spent on physical integration and not enough on social integration. However it is heartening that residents have now set up the Friends of the Greenway group to take on maintenance. Significantly perhaps, the development of the later plots attracted almost no comments according to the Head of Planning at Brighton and Hove Councils who was there to observe the discussion.

Achieving quality

The scheme is made up of contemporary mid-rise blocks, with many interesting views. Involvement of many different architects within a series of Design Codes has resulted in a Variety of architectural approaches. The entrance to the Sainbury’s is from a square although this is not yet busy. Cars are hidden away underground and there are just 15 parking disabled parking spaces for the 172 flats in the BioRegional scheme, so the development is one of the largest car free schemes in the UK. As a result it feels quite quiet, though the food store generates life at all times. Public art, such as the ‘ghost train’ over the railway bridge seeks to interpret the site’s history as a place where locomotives (and Pullman carriages) were once built. The spaces need better maintenance, though a Friends of the Greenway group is now helping look after it. QED handed over the site hoardings to some 120 local ‘graffiti writers’, which made it more interesting during the long construction period.

Acting as an exemplar

The Life Cycle Assessment report of the carbon savings in One Brighton found that they achieved a 60% reduction compared with conventional homes, which could go up to 78%. More could have been achieved if the biomass boiler had served a larger development (as URBED originally planned). BioRegional have been able to apply their ten One Planet Living principles in a prominent scheme which others have taken up. They are now working in fifteen different countries, and influencing many billions of investment. One Brighton has been carefully evaluated, and there are many lessons for those trying to reduce energy consumption in new housing schemes. Design Council CABE is trying to carry on the role of sharing good practice, but no longer receives a government grant. With so many senior people having left local authorities, unless it can be made much easier to secure higher quality standards, the potential for replicating the New England Quarter around other major railway stations may go unrealised. Hence URBED must continue to share the lessons as widely as possible. Conclusion Clearly masterplans and development frameworks can help produce agreement on complex schemes that can only be implemented over several decades, and even raise quality standards. But if government seeks to cut redtape in a ill-considered way without providing a means of providing upfront infrastructure, the prospects of replicating the New England Quarter look poor.

Nicholas Falk July 2015