Fostering innovation and new work

This is the second set of impressions from a three week return visit to California and the North American West Coast in which my partner Esther and I travelled from Vancouver in British Columbia to Palo Alto in Northern California, a distance of a thousand miles. This one deals with how the USA came to lead the world in information technology, while lagging in personal mobility.

The keys to successful innovation

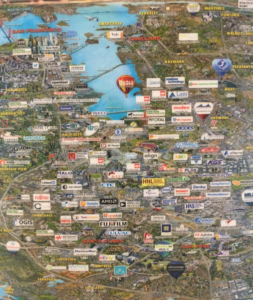

Why has the ‘fourth industrial revolution’ based on Information Technology been so concentrated along the American West Coast? After all it could have been in Europe, in cities such as Manchester, where the first working computer was built, or in Nice, where the warm weather rivals that of the West Coast. Much of the answer is set out in a brilliant book The Innovators by Walter Isaacson, (which I read on my Kindle as we toured the West Coast.) Isaacson, who once chaired CNN and was former Managing Editor of Time magazine, has unpacked the stories of each of the main innovations and their inventors, from Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace to present day giants like Bill Gates and Paul Allen, who turned Seattle into a high-tech hub. An intriguing timeline in Isaacson’s book shows how they were linked before production shifted to the East. A ride on Seattle’s trams shows how talent and capital are being attracted back from the Far East.

Isaacson explains that not only were the great inventions typically the product of small teams rather than individuals, but also the climate or culture of an area shapes what happens with inventions. The West Coast temperament is much better attuned to experimentation and recovering from failures and setbacks than the conservative and cold East Coast. The pioneering tradition described earlier partly explains the success of the post-war pioneers in information technology such as Hewlett and Packard, or the men who built up Fairchild, or more recently Larry Page and Sergey Brin, who set up Google. They were all graduates of Stanford University, which was built on land donated to commemorate Leland Stanford’s son, and which has done so much to spawn the fourth industrial revolution. The tech entrepreneurs wanted to create work that allowed them to live on the relaxed West Coast and make an impact on the world. In turn this created a magnet for innovators like Mark Zuckerberg, the Facebook founder, whose motto was ‘Move fast and break things’.

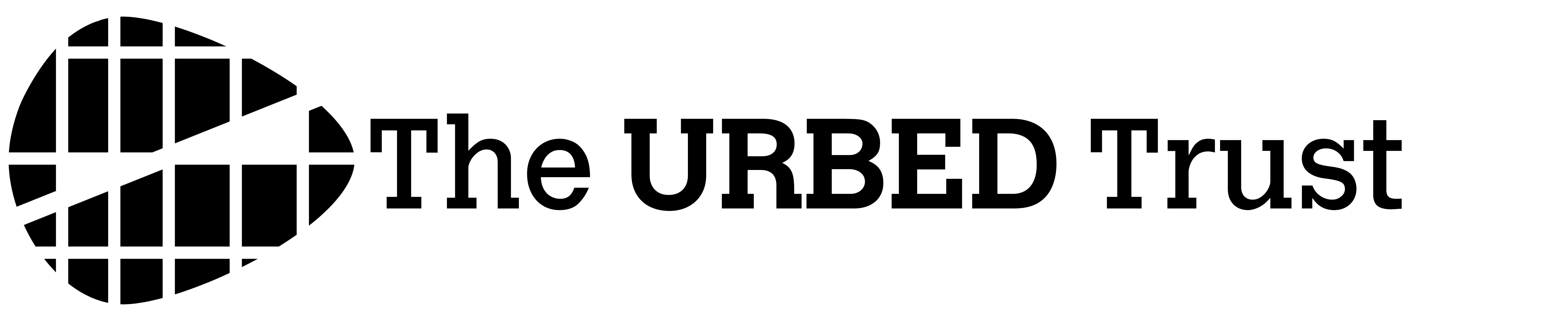

Origins of Silicon Valley

The term Silicon Valley was coined around fifty years ago. The invention of the minute silicon chip that replaced the slow and bulky electrical valve, enabled giant companies like Xerox and IBM to service the demands of the American government, and enabled the USA to send the first man to the moon. One wave tends to follow another. Even with the power of IT, human interaction is also vital. Harvard economist Professor Michael Porter has proved, clusters matter. Smart people tend to live near their peers or mentors, and trade with each other. The man who turned Stanford from a rich man’s finishing school into what is now widely regarded as the world’s leading technology university was Fred Terman. He started as a professor of electrical engineering before returning after the Second World War as Dean of Engineering, when the university’s main asset was its landscape. He recruited innovators such as William Shockley. Shockley claimed to have invented the transistor, an electronic microswitch, on his own when he was at Bell Labs. Shockley was so unpopular that his colleagues left and turned Fairchild into the first volume ‘chip’ manufacturer, an unplanned but crucial step in the path of innovation.

Terman’s prevailing ethos for Stanford, unlike that of Harvard and MIT on the East Coast, was to encourage academic staff to work with students to get inventions into production. The role of ‘mentors’ has remained important, as I was assured by one of the most successful business founders and venture capitalists from my class of 1969. Clearly the availability of people with advanced technical skills prepared to offer excellent advice and encouragement freely in the early days before businesses can pay for consultants gave the West Coast a real edge. So too did the practice of beaming university lectures directly to local employees of hi-tech firms so that courses could be audited or taken as degrees. Venture capital and law firms then provided the funding and expertise to take good technical ideas to commercial fruition. A complex business services sector grew up on their back (unlike the situation in potential European rivals).

Assuming the role of university Provost, when the only resource Terman could mobilise at the time was land, he made space available for three important ventures. First came the Stanford Shopping Centre to generate income and meet student needs. Second came Stanford Research Institute (SRI) to capitalise on inventions, and link research and development. But most important of all was the Stanford Industrial Park, which has led to a crop of science parks around the world, none of which have achieved the same success. Today 80% of the university’s sponsored research budget of $1.6 billion in 2019 comes from the government in 6,000 different projects, with medicine accounting for two-thirds. Successful graduates give money back to the university to endow fine buildings. But 50 years ago it was electronics where the key breakthroughs were made.

Waves of innovation

The first wave of innovation took place in the ample garages of Palo Alto and neighbouring Menlo Park. This is where pioneers like Hewlett and Packard, the real ‘technology innovators, but later Steve Jobs and his original partner Steve Wozniak first made their names. A second wave of business transformers such as IBM and Xerox changed the way business worked. They first moved into purpose-built offices and production space in the science parks along the main roads. These providing space where companies could impress their customers, typically in the early days the US military and then the space programme. The name Silicon Valley no doubt gave government customers the confidence they were in the right place for buying yet unproven technologies. I was told at the time the international companies wanted to locate where it was easy to attract (or lay off) good staff, and where ‘their wives could audit courses such as art history’. This changed once women moved out of the kitchen to take on leading roles! IBM at one time employed 13,000 workers in its campus at San Jose, before shifting production to China after some 50 years in the early 2000s, though their research centre has remained

The third wave, who might be called the ‘world changers’, or ‘business disruptors, accommodated the major consumer oriented large companies such as IBM and Xerox, who transformed the way offices worked, and their successors such as Apple and Google who created completely new consumer products and services. They built campuses for their staff taking over cheap land on the edge of the built-up area. In the early days private developers built thousands of detached suburban houses. Today some of their redundant industrial land is being turned into higher density apartments. Google’s owner Alphabet is planning its own ‘Smart City’ on a lakeside in Toronto. Meanwhile a whole web of companies has grown up around Microsoft in Seattle.

Most recently a fourth wave can be discerned in the massive towers around Salesforce Park, which had opened two months before our chance visit on the top of San Francisco’s new transit hub. These are occupied by what some refer to as the ‘global disruptors’, who lease space from property companies. The whole area is being redeveloped after the last earthquake in 1989.There is even said to be a kind of PayPal ‘mafia’, with lots of interconnections, and perhaps a new set of robber barons in the tradition of Leland Stanford. Today’s techies, or their salesmen at least, like to live in city centres rather than the suburbs, yet despite starting salaries of over $100,000, can only afford to lease their apartments. They certainly could not afford to live around Stanford any longer. Many seem to be moving even further out to cities such as Seattle, where despite the wet climate all that a hi-tech employee might want is on their doorstep. Eating out seems to be the norm.

Social consequences

The patchwork of predominantly small local authorities with populations as low as 67,000 in Palo Alto, though well-intentioned, are no match for the economic forces at work. Their size makes it difficult to collaborate across borders and address social inequalities and elitism. Nor do they seem to be able to secure integrated transport. Nowhere in the region came close to meeting the targets for housebuilding that have been set. So though the Bay Area was a leader in tackling greenhouse gases, it was a loser when it came to foreclosures, that is the repossession of houses whose owners had defaulted on mortgage payments.

The persistent and growing contrasts between the lives of the rich and the poor are most evident in the big cities but also apply to the wider state of California. The failure to apply technology to create fully integrated transport systems or truly affordable housing, reveal a basic flaw in the American capitalist system. It is what economists refer to as the ‘tragedy of the commons.’ Using the example of over-grazing, individuals pursuing their own interests can result in everyone ending up worse off. The financial markets overvalue tech companies, and investors in companies such as WeWork or Uber are unlikely to get their money back. Meanwhile local authorities remain under-resourced because of voters’ resistance to higher taxes.

As is evident from the large numbers living on the streets or in vans, the market system that prevails in most of California offers no safety net for those unable for one reason or another to compete for living space. The vast revenues of the tech ‘titans’ dwarf those available to state authorities but do little to counter the housing crisis they have indirectly caused. Attempts to build tech. utopias, as Google is trying in Toronto, are resisted. The property values of newcomers such as Google and Facebook in Santa Clara County are nearly as valuable as those of Stanford University, with its much larger land holdings and over 130 years of growth. Apple has been described by FT columnist Martin Woolf as ‘an investment fund attached to an innovation machine and so a black hole for aggregate demand.’[1] The situation is therefore inherently unstable, with huge funds floating round the world in search of low risk tax havens.

Business Schools as incubators

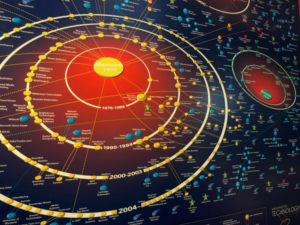

The role of the university is still important in creating new work. Universities such as Stanford (which comes second on some global rankings) do so by attracting the best qualified faculty and students from all over the world. Undoubtedly the beautiful climate and cultured surroundings help. In returning to the Graduate School of Business we were given excellent presentations on leadership and diversity. But I recalled that it was the teaching methods of debating real-life case studies that had originally given American business schools their lead. Today more attention is being placed on learning communication skills and on self-development or leadership. There is much more emphasis on creating your own business or social enterprise. The idea of training students to tackle local environmental or social problems seems to have lapsed.

Fifty years ago Stanford University was rocked by student protests about contracts from the US government to Stanford Research Institute (SRI) for work on counter insurgency and chemical and biological warfare, which accounted for some 10% of their turnover. I was one of a committee that came up with proposals to sell SRI to its staff, with constraints on the work it did, and a Marxist economist was recruited from Cambridge by student activists. The Vietnam War and its expansion through other parts of South East Asia, the space programme, and Reagan’s defence build-up in the 1980s led to private companies along the West Coast gaining a commanding lead in technologies that came to dominate the world. It seems the radical thinking that inspired the Whole Earth Catalogue and a host of innovative rock bands has petered out.

Government procurement still lies behind most of the innovations that we take for granted from the Internet to the touch screen. It was no coincidence that so many of the pioneers knew each other, like the founders of Google, because they came from the same town or went to the same university or school. But it was government money that paid for R&D. Today 90% of Stanford University’s research budget is for medical research. The many business successes are commemorated in the exceptional buildings that have been donated, such as the Knight Building from the founder of the footwear company Nike, which is based in Portland. Sponsored fine art galleries and music centres along with the best ranked teaching make Stanford University a world leader on many scores. Great job prospects, especially for those doing engineering, give it a commanding advantage over the European equivalents such as Cambridge, let alone Manchester, which is being promoted as the ‘MIT of the North.’

So though Stanford Business School must be commended for establishing a programme to help people in developing countries build successful businesses, without equivalent action to reform their financial institutions or local authorities the results are likely to be ineffectual. The West badly needs new models for tackling challenges such as climate change or affordable housing if it is to maintain its lead as a place to live and work. Perhaps the IT industry should enable the lessons to be shared with the rest of the world?

The West Coast is the most advanced part of the richest country in the world. The value of shares in recent start-ups are greater than the corporate giants that have survived the centuries, such as Ford Motor Company, The cities of the North American West Coast North of Palo Alto are without doubt great places to visit and live in, not least because they are bordered by the sea on one side and hills or mountains on the other. Their attractions to people from all over the world help to explain the dominance of the USA in several fields, especially in Information Technology and its related products and services. The role of science parks should be seen as incidental.

However, what the great American economist John Galbraith referred to as ‘private affluence and public squalor’ still applies over half a century later and holds back future growth. Governments urgently need to find innovative ways of tackling environmental and social issues, and sharing lessons on urban development between East and West before the mistakes are repeated on a global scale. The methods Stanford uses to create business leaders could equally apply to training the leaders of social and environmental change.

As ever, Nick, fascinating and a pleasure to read.

All we need now is a solution to the dilema you so ably describe. Howard’s land ownership methodology for garden cities driven into existance by climate change threats?