Bridging the gaps

Three days in the historic university town of Grenoble with a group of academics, council leaders and others from Oxford was a truly memorable experience. The colloquium also provided a fantastic opportunity to consider what makes a medium-sized city ‘great’, and to learn from their pioneering LIFE programme about effective cross-disciplinary research. But the three days as their guest also raised the issue of how to promote equality and how to use spatial planning to make cities work better for all.

A great ‘metropole’?

Grenoble is like Oxford in many ways. With a population of around 160,000, but part of a metropolitan area twice that size, the city grew rapidly in the early 20th century on the back of industrialisation. It turned from glove making to industries based on hydro power, and Grenoble became one of France’s main ‘high tech’ centres, for example inventing reinforced concrete. The university became renowned for technological training and research. It boasts one of France’s largest architectural departments, who were our hosts thanks to the energy and genius of Stéphane Sadoux who runs the unit there.

Also like Oxford, the city is long and thin, but bordered by the real barriers of mountains, not the artificial ones of local authority boundaries and a Green Belt. Some congestion and pollution is consequently inevitable, and creates real health problems. Grenoble was the first city in France to reintroduce trams some thirty years ago to get cars out of the centre. With an extensive tram system of four lines, integrated with busways, the city has sought to tackle pollution at source. The high-speed railway gets to Lyon in half an hour, and puts Paris just three hours away, cutting the need to use air transport.

Grenoble’s Green Mayor is going further in banning cars from the centre and making cycling easier. The Metropolitan Council closely monitors air quality and restricts commercial vehicles on the most polluted winter days. Even then, cars still account for 55% of trips to work, with public transport carrying 25%, and bikes only 5%. So at the start of an event with some 30 speakers, the Mayor, Éric Piolle explained how the City was taking a holistic and integrated policy that brings together people and place. For example Grenoble was the first to employ ‘health mediators’ at day care centres and schools. It is innovating in building techniques, for example using rammed earth. The Mayor believes ‘housing is the central pillar of health’. The City has won awards for building one of the first Eco Quarters in France at De Bonne with 900 apartments on 15 hectares, and is now aiming to do still better at ZAC Flaubert.

The President of Grenoble Alpes Maritime (which covers a similar area to Oxfordshire) stressed the importance of spatial planning to mobility, air, economic development and food, and hence wellbeing. The Chancellor of the University and Director of the Architecture School both saw the solutions at the interface between disciplines, hence the importance of bringing institutions together. Their university is tackling health in the urban environment through collaboration between cities and universities on societal issues, and Grenoble sends its students to England to learn about garden cities.

LIFE is made of choices

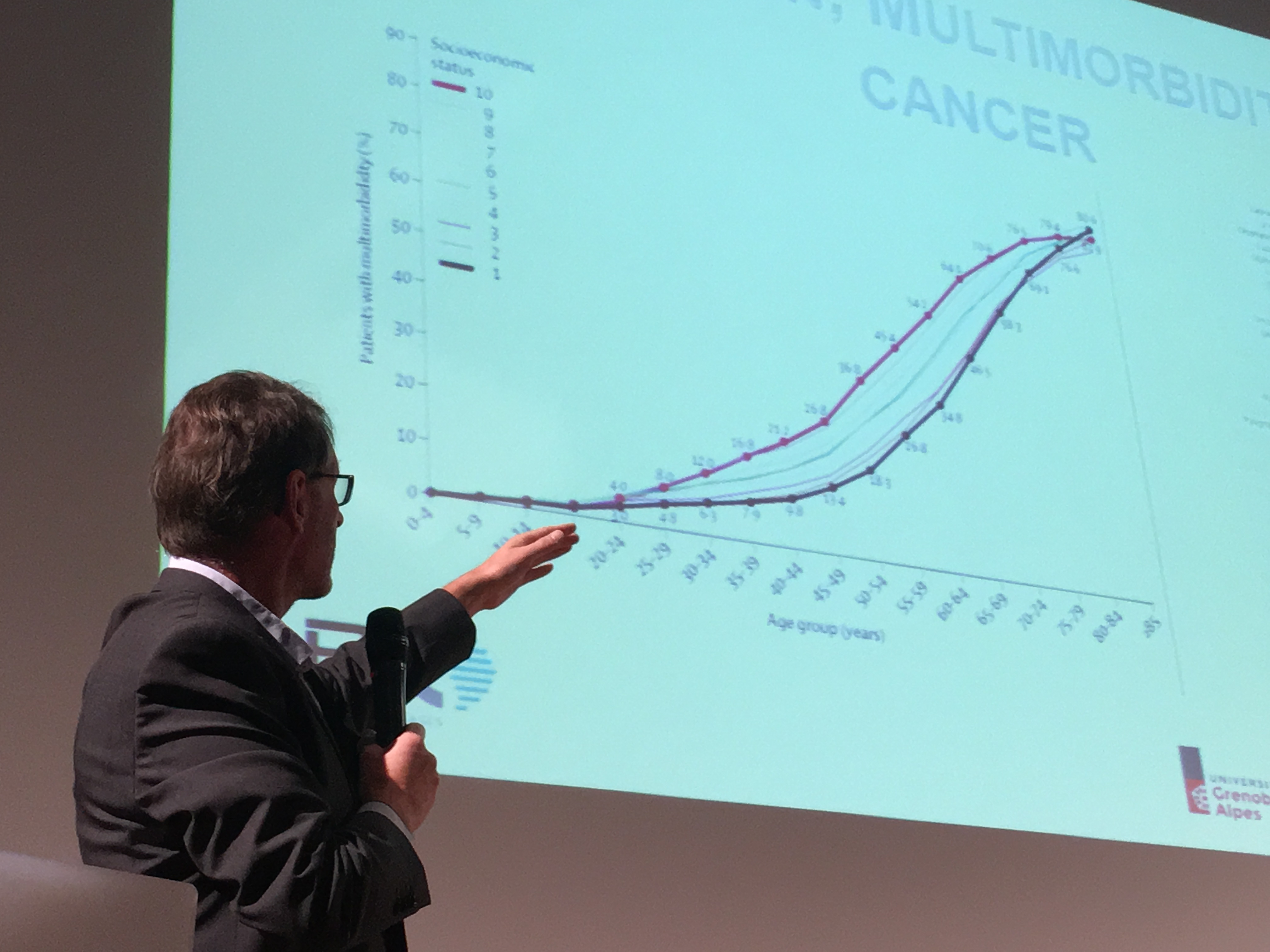

This ambitious programme, which brings some 100 researchers from ten different departments together, is driven by the knowledge that conditions are inter-related. For example poverty and polarisation is induced by lack of finance, and multiple morbidity imposes high costs on the health service. People in marginalised communities have double the risks of ill-health, as diseases are clustered, and their causes can now be identified through trans-disciplinary mapping. Solutions include active travel, green space and the production of healthy food, and the co-location of services in community hubs. Municipal health plans translate the findings into policies that create real ‘eco cities’.

One of the greatest challenges is that the population is ageing everywhere, as the Director of the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing graphically showed. Furthermore the greatest demands on health care are made by the very old. Consequently we must ask what kind of places do we want and how we can live better with perhaps 50 years of ‘retirement’ to look forward to. In Grenoble the numbers of elderly are increasing by 1% a year. Challenges such as isolation could be tackled through apartments with shared services, renovation to tackle the problem of fuel poverty (which afflicts 15% of residents in Grenoble) , ‘human powered mobility’ , and the mobilisation of more volunteers to combat isolation. An ‘energy transition plan’ can simultaneously tackle the issues of poverty and ill-health caused by air pollution, which kills 20,000 a year in the UK, or ten times the numbers killed on the roads.

Health can also be improved through greater use of solar panels instead of smoky wood fires, local energy systems fuelled by municipal waste, and incentives for low-polluting cars combined with locating car parks on the edge. Emissions can be limited through thermal retrofits but also be creating ‘cooling islands’ with plenty of vegetation to bring down extreme temperatures in the Summer.

Rebalancing our cities

With people living much longer and no longer working close to home, much more has to be done to reduce the disparities between different sides of a city, as well as between the relatively rich and poor. Both Grenoble and Oxford face huge spatial inequalities, as poorer people end up in areas with high levels of social housing where they can feel trapped. Regrettably we heard that in the UK cutbacks to local authority finance have led to the closure of the very childen’s centres, social care and services such as Dial a Ride which are most needed. A fragmented structure makes it harder to join up services, and tackle the causes and avoid ‘fire-fighting. So where there new developments, it is all the more important to innovate, as the NHS Healthy New Towns programme aims to do. But how success should be measured was one of the questions arising from panel discussions where cross-country collaboration would be really useful.

Everyone agrees that team working is vital, particularly in tackling the causes of inequality. Segregation creates stress, which not only cuts life spans but also leads to violent behaviour. After the conference, visiting the vast 1970s quarter called Villeneuve, or New Town, I was depressed by the sheer brutality and anonymity of many of the buildings. Not surprisingly few of the students at the large Architecture School based there choose to live nearby. Attempts are being made to humanise the area, for example cutting slices out of the long slab blocks. But a beautiful park, a tram stop or a modern community centre are not enough to give people hope for a better life. The High School had been set on fire a few months earlier, and there is talk of racial conflict.

Working for the common good

Grenoble would not be a city without a great university and transport hub, but surely the real test of a great city is whether it works for all? The challenge now is to get to the ‘roots’ of problems, such as health and deprivation, while rediscovering the ideals of the ‘Garden City’ (Stéphane Sadoux’s passion). The great challenge as people live longer, and come from diverse backgrounds, is how to create and maintain urban neighbourhoods in the face of limited public finance.

One solution is to pull down the worst buildings, and create places that offer better lifestyles so that cities attract and retain wealth creators. Grenoble pioneered one of the first Eco Quarters in France 15 years ago at De Bonne, in the heart of the city, which has won many prizes. It is now developing several thousand new homes at ZAC Flaubert on the tram line to Villeneuve. This is a public private partnership where the city is only allowed to invest 30-40% of the costs, the rest having to come from private investors. Serviced land is sold to builders at prices that depend on the use. The new quarter will halve energy consumption through a ‘circular economy’. An old railway line forms the spine of a new park, and extensive planting will keep temperatures down in Summer, while the new school is being cooled by underground water. There will be a market garden on top of a car park.

However as one of the British speakers pointed out, there is a danger of building obsolete cities that cannot adapt to changing lifestyles and patterns of work. For example of 50,000 pieces of research into autonomous vehicles only 16 looked at the interaction with pedestrians, and the new cars may be unsafe in the centres while unable to move in the suburbs. While we cannot know the future, or the impact of different technologies, surely we can build and maintain urban frameworks that encourage collaborative lifestyles, whether it be through street cafes in the heart of the city or arts and community centres in the suburbs. Resources will never be enough, so we have to share knowledge and experience, as this colloquium did so well. Looking and Learning pays dividends. All who took part will want to strengthen the links between these two potentially great cities.

I’m surprised to learn that architectural students don’t live in Villeneuve, as usually they are the first to appreciate out of fashion architecture. For example, architectural students squatted in derelcit terraced house which had been condemmed in Camden, and also occupied Le Corbusier’s Unite d’Habitation to prevent its demolition.

Students and young people can be a very poweful force for regenerating ‘unacceptable’ areas, as they are more than happy to tolerate conditions others would not in return for an interesting environment. And once the local population realise that there are large numbers of people around who actually want to be there, the perception of the whole area alters and the desire to leave evaporates. This is how sink estates around Brixton were rescued, by allowing people who were not on the Council waiting list to move in provided they agreed to live there all the time. Within weeks the estates werer permanently full and vandalism ceased.

The trick is to use a local venue to put on events to which young people are attracted (eg. big name DJs or bands) even if the gigs only break even. That way the youth become used to going to the area, and are keen to take accomodation there even if it is not superficially attractive. It’s the ‘vibe’ that counts.

What is required is an entrepreneur or switched on council empoyee with a small budget who really understands youth culture. Magic can follow……..