Creating a model for smarter urbanisation

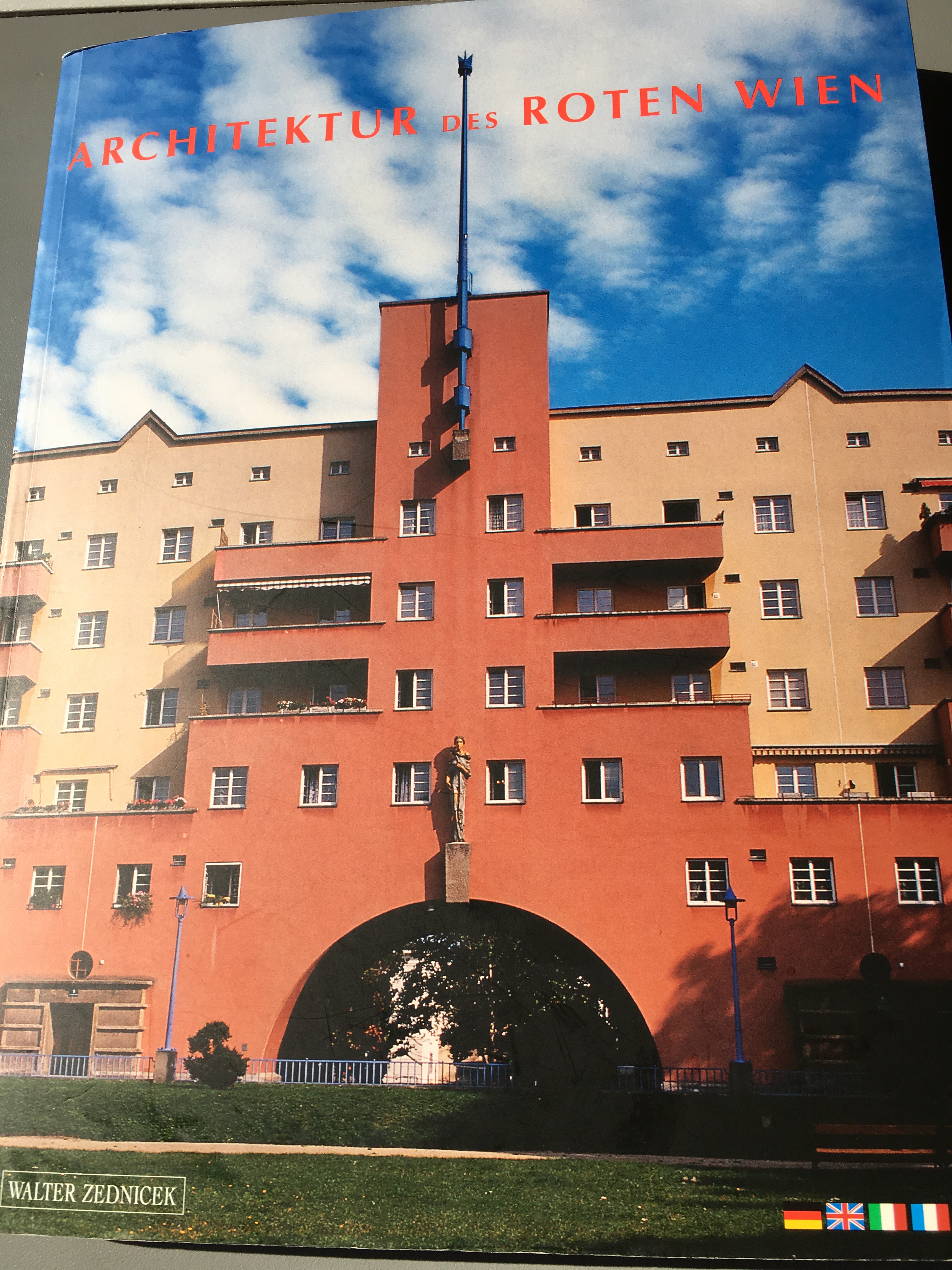

Vienna has undergone a transformation since the bleak days of The Third Man, and now regularly tops the polls as one of the world’s best cities. Mercers, for example, have rated it number one from 2011-17. Yet the Lonely Planet Guide as recently as 2007 was complaining of the excessive amounts of beggars and dog poo! The City benefits from the long socialist tradition of ‘Red Vienna’ which has left a legacy of publicly owned housing, transport and green spaces, and iconic buildings such as Karl Marx Hof. The Vienna Woods and other mountains form an effective ‘green belt’ round much of the city, and any land that is taken for building has to be replaced elsewhere. Some 45-50% of the metropolitan area is green out of a total area of 415 sq km.

Vienna enjoys a legacy of great buildings along the Ringstrasse

The heart of the city is made up of high density blocks of flats along streets, which support a high quality public transport system. Indeed according to The State of European Cities 2016, Vienna has the highest use of public transport of any European city (followed by Zurich). Vienna also stands out for reducing car use, from 40% of trips in 1993 to 27% in 2012, whereas London went 46% to 38% over a similar period, as did Paris. So it is perhaps not surprising that Vienna is in the top ten of European capitals in terms of life satisfaction, and also performs well on other measures such as GDP per capita.

With a population of 1.8 million, some 25% of the Austrian total, Vienna functions not just as a capital city, but as part of a wider network of industrious and green cities from which others can learn. In a visit with the Urban Design Group, we found out how the City is developing plans for STEP 2025 through three themes: ‘building the future; reaching beyond its borders; and networking the city.’ What stands out to the British visitor is not only the City’s success in taming the car through a superb integrated transport system, but also keeping such an attractive city affordable through their approach to building homes for rent, including several stylish new quarters. Indeed the city seems remarkably homogenous.

Connected cities

Vienna was once the capital of an empire with 50 million inhabitants, and is exceptionally well-connected with the rest of Central Europe. Capitals such as Prague and Budapest are only an hour or so away, and Bratislava is only 60km away and attracting a lot of less-skilled manufacturing work. Austria has much in common with neighbouring Switzerland, and the mountainous valleys encouraged early industrialisation and railway building. Frequent trains operated by Austrian Railways and its partners such as Hungarian Railways link the main cities of Graz, Linz, Salzburg and Innsbruck. The train trips reinforced a strong image of Austria as part of a dynamic European Union with a thriving economy. Every small town shows off its modern factories on the outskirts, often with their own sidings, and so the lines are used to capacity.

One of the best public transport systems makes it easy to get around without a car

In addition to large long-distance trains going through to Zurich, Prague or Hamburg for example, there are also plenty of modern local trains connecting up suburban stations. With low fares and frequent services, the railways play a large part in improving urban quality, and making it attractive to live in towns. There are 225km of tram and 79km of underground lines, and the travel pass also applies to the train lines and buses, with no barriers and few ticket inspections.

3 million live in the greater metropolitan area of Vienna and the current modal split is 39% public transport, 28% walking, 6% cycling and only 27% motorised. The ‘urban mobility concept’ is that 80% of trip will be eco-friendly by 2025, and only 20% by car. The greatest achievement has been the pedestrianisation of some 430 metres of the main shopping area, Mariahilfer Strasse, while a further 1200 metres is an ‘encounter zone’ in which pedestrians take precedence. The whole area within District 1, which has a diameter of about a mile, is largely traffic free. This contrast vividly with places such as Oxford Street which is dominated by buses crawling along, or Trafalgar Square. Like Freiburg, Vienna promotes itself as a ‘city of short distances’. Pedestrians cross at the lights because you do not have to wait long, and the streets seem very orderly.

The main stations have been rebuilt several times, and act not just as transport hubs but also as commercial centres. The buildings themselves are simple and functional, not architectural icons, so that the investment has gone into rail services. Thus Vienna’s Hautbahnhof has been turned into a through station, and the railway yards around it have been redeveloped at high densities for a mix of uses. It is very easy to connect between one mode and another, with trams and buses sharing the same platforms in smaller cities such as Innsbruch, whereas in Vienna the trams go underground. Excellent information systems and generous concourses make interchange easy. By building down and developing the underground space for shopping, including vast supermarkets, the stations serve many purposes and facilitate movement between both sides of the tracks.

The main station has been redeveloped as a transport hub

Affordable housing for all

Most people live in apartments, and Vienna stands out as a city that has largely avoided house price inflation. Housing costs are relatively low (around 25% of incomes?) thanks to 80% of homes being rented, of which 60% are owned by the City, whose aim is to keep housing costs down. The municipality owns 220,000 flats, and there are 330,000 social housing units in total. 60% of the housing stock was built before the First World War, and the City built 63,800 units between 1923 and 1933, some of which, like Karl Marx Hof, are internationally known. Space standards are rising, with an average of 34sq m per person now compared with 27sq m 20 years ago. Along with a rising population, the City needs to build 10,000 homes a year to keep pace.

High density apartments have made good public transport viable

Housing is managed by a number of different bodies such as housing associations and cooperatives, and many of the new blocks have a mix of tenures in them. There is a city owned development agency which acquires land and assigns sites to developers (the Wohnsfond Wien). The aim is to secure a balance, though the Municipality may now have high levels of debt. The key to viability is that the City caters for middle income families. Much of the new housing has been provided through redeveloping brownfield sites such as railway yards or infill buildings, but they are now starting to face the challenge of developing on privately owned land, and land value taxation is a subject of political debate.

New urban quarters

The City has taken the lead in promoting a number of high quality schemes around the stations. 100 ha is being redeveloped at the main station, where there will be 13,000 residents and 17,000 jobs. Nordbahnhof, the Northern railway station is being developed over the period 1994-2030 for 20,000 residents and a similar number of jobs around a large central park with play facilities for children. The blocks of apartments are all very different, and tend to have commercial space on the ground floor, four floors of social housing and two that are privately owned. There is already a wide range of shops and cafes, as well as a number of major employers.

The yards of other stations, like Nordbahnhof, have been turned into high quality residential areas

The most ambitious scheme is the redevelopment of Vienna’s old airport as Aspern Seestadt, or lakeside. Built around a 4.5km extension of Underground Line U2 which was opened in 2013, four years after the start of work, it comprises 240 ha. It is being developed over the period 2005-20 for 10,500 dwellings with 25,000 residents, and some 20,000 jobs. Very imaginative landscaping, as well as the water areas is turning a peripheral location into a desirable area, which is particularly popular with young families. The idea of the lake was to avoid having to bring building materials in, and this is just one way in which Vienna is demonstrating its credentials as a ‘Smart City’. All the housing so far is in the form of apartment blocks but all look very different, and relate well to the streets and adjoining green spaces. Indeed some space is given over to growing food, so that town and country are reconciled.

Half the new space in developments such as Aspern Lakeside is green

The City is now building Underground Line 5 to open up more of the North Western part of the city to development. Transport investment is jointly funded by the City, the Province, and the national government. With a growing student population (200,000 currently) and some immigration (21% of the population were born abroad, and the City Deputy Mayor for Planning is herself Greek), Vienna may be facing major challenges in future in keeping housing affordable. There could be resistance to expansion from the strong Right Wing parties in the surrounding countryside, which suggests there may be similarities with the situation in London.

Enterprise and innovation

Vienna has a thriving economy, and 103,000 still work in the ‘production and distribution of material goods’. There seem to be no empty shops, (which applies to all the cities we visited). The spaces that would have been vacated when the main shopping area was upgraded have found new uses as ‘Concept Shops’ run by very creative entrepreneurs. A useful leaflet helps to promote knowledge of their existence, as does the relatively low costs of some E12,000 a year that includes heating and property taxes.

Shopping is an enjoyable experience

Vienna now has an attractive ‘alternative’ area near the main market called Freihaus Viertel, which has only taken off in the last four or five years. With low housing costs, residents have more to spend on furnishings or clothes, which in turn must create opportunities for the many small businesses that make up the local economy. Vienna is also promoting the ‘green economy’, and for example there is a technology centre located at Aspern Seesdadt called Aspern IQ as well as Vienna’s largest social service employer.

But Vienna is also a major financial and trading centre, helped in part by its excellent universities, and notably its economists. The Vienna University of Economics and Business has some remarkable buildings, several by British architects. As with other capital cities there are several hundred thousand students, and efforts are being made to encourage spin-offs that will help retain the ‘brain power’ the city attracts.

Enterprise is encouraged through affordable space.

Living heritage

The countryside is never far away, and some 12 different types of green space are designated in the City’s plans, including ‘lively streets and pedestrian areas.’ Vienna boasts 100 museums, and has an extraordinarily rich heritage of grand buildings in the central area. As well as the many imperial buildings, rich Viennese businessmen built palaces for their families along the Ringstrasse, which replaced the old City walls between 1860 and 1890. Designated by UNESCO as part of Vienna’s World Heritage Site, it provides a place for locals to promenade as well as for tourists to wander or ride the tram. The buildings have all been restored, and many are now grand hotels, while others include the main Opera House, and art galleries with world famous collections.

The Prater, with its iconic Ferris Wheel, still provides popular entertainment, as does the Danube. So, not surprisingly, Vienna is one of the most popular tourist destinations. All the streets are now very clean with no graffiti or vandalism (contrasting hugely with what we say on the train ride from Basel to Strasbourg in France). This suggests an underlying sense of order or collective action within which individualism can play out, rather than a market dominated system, as in the UK.

Smart city planning

At the start of our visit we were given a presentation, with some excellent short cartoon films, on the new City plan STEP 2025, which was adopted in 2014. This sets out some basic values to provide a city wide framework, with a focus on ‘crossing borders’. There are separate sections for eight thematic topics, such as Production areas, or Local and business centres, and these are grouped into three sections: building the future; reaching beyond its borders; and networking the city. So taking the Urban Mobility Plan, which is one of the topics, this starts with the objectives of being fair, healthy, compact, eco-friendly, robust and efficient. As an example of a practical policy, in Aspern Seestadt, a Mobility Fund is supported by not building garages, which is used to pay for eco-measures, such as car sharing.

Development is guided by the STEP 2025 planning framework

Considerable stress is placed on engaging with the various communities through ‘an intensive dialogue with numerous experts.’ Communications are excellent, with the use of short animated films to explain difficult concepts, and short reports in English. STEP 2025 is designed to provide a strategic framework for local plans through a polycentric city that makes the most of under-utilised land in the outer areas. ‘Target areas for development’ are identified where collaboration between the different sectors is key through ‘implementation partnerships.’ Significantly the STEP 2025 report concludes by emphasising the importance of reaching beyond the borders: ‘Key elements of this task include close consultation on all issues of regional planning (e.g. co-ordinated development along public transport axes, fine-tuned active land management policies’).

Conclusions

Though Vienna’s position and cultural heritage are very special, all the Austrian cities we visited shared excellent integrated public transit systems and compact high density residential areas and possibly a similar set of values, with pride in their past and future. Vienna, as the capital of one of the many small European countries, clearly sees the importance of collaboration across borders, and shows how more proactive municipal leadership can work to everyone’s benefit.

Thanks, Nick. As ever, really useful and inspiring.

It seems as if the Austrians have embraced New Urbanism very vigorously. It would be useful to know more about how the public transport system is funded. Does the central government make a large contribution from general taxation, or is there a specific transport related tax as in Paris?

The other question is about suburbs: are they growing also? Or has all the development you describe mopped up demand so that little suburban development occurs because there is not demand for it?